Book review: Martin Bailey, The Sunflowers are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh’s Masterpiece…

by The Frame Blog

…including additional material on the frames of Van Gogh’s sunflower paintings

Martin Bailey, The Sunflowers are Mine: The story of Van Gogh’s masterpiece, published by Frances Lincoln, September 2013, pp. 240, 100 colour ill., £25.00

The decision to write a book solely about Van Gogh’s paintings of sunflowers may seem from outside its covers a wilful circumscribing of a subject; I knew that there were several of them – three or four, perhaps – but a whole book? Martin Bailey’s eye, however, is acutely attuned even to the smallest sunflower plant in a particular landscape, and to the faded, age-browned yellows melting into the backgrounds from which they would once have sung sulphurously. It is also marvellously alert to the freshness of a life seen through a tightly focused lens.

It turns out that there were a great many sunflowers. Four paintings of cut seed heads, executed in Paris in 1887, and four different arrangements in vases, with three copies, from Provence in 1888-89; as well as a mixed bouquet, views of fields and gardens around Montmartre, studies of single plants and groups, gardens and flowerbeds in Arles. No wonder that Van Gogh could write to both Gauguin and his brother, Theo, pointing out that whilst other artists had annexed the peony or hollyhock, ‘…j’ai avant d’autres pris le tournesol’ – the sunflower is mine.

Letter from Van Gogh to Gauguin, 21 January 1889, Musée Réattu, Arles

It became an index of his journey from the dark palette of his early paintings in Belgian and the Netherlands, under the influence of The Hague School, to the brighter uplands of Paris and the Impressionists, and then to Provence. His life previously had been a series of starts and stops and stalls; he had worked as an art dealer in The Hague and London, as a teacher, a bookseller, and finally as a preacher in a Belgian coal mining area. His subjects were as bleak and dark as his paints, and Paris must have opened before him like a revelation, the city and the artists bathing equally in light and colour. He began to paint his immediate surroundings, using a purer mix of colours and introducing the sunflowers which seemed to grow everywhere in the rough fields and allotments of Montmartre.

Monet, Bouquet of sunflowers, 1881, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.107). Photo Wally Gobetz

They were popular flowers to grow and to paint; Monet had already produced a still life of home-grown sunflowers five years before Van Gogh arrived in Paris. These were soft, fluffy and hectically-coloured, very different from Vincent’s sunflowers, with their awkward, spiky solidity. Monet’s painting could not have been seen by Van Gogh (although he was later told about it by Gauguin), as it was bought the year it was painted by the dealer Durand-Ruel and sold by him successively to three American collectors. This explains the late Régence style of the current frame (the way to sell the Impressionists in the 19th and early 20th century was to package them as Old Masters; see ‘Antique frames on Impressionist paintings’) .

Van Gogh’s flower paintings of 1886 were at first in the vein of Monet’s work, including an impressionistic earthenware vase of roses and sunflowers.

Van Gogh, Two cut sunflowers, 1887, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1949 (49.41)

Then, in the late summer of 1887, he homed in on his subject, producing four paintings of cut flowers on a table, the wilting petals in retreat from the vast heads with their whirling arrangement of seeds, like alien suns caught in a space storm. The third of the series, above, is placed – unlike the earlier two – on a blue ground, against which the golden petals zing and vibrate. As Martin Bailey notes,

Van Gogh saw these as the colours of the season. “Summer is the opposition of blues against an element of orange in the golden bronze of the wheat,” he had written three years earlier.

This and the first of the four seed-head paintings were exhibited in November 1887 at the Restaurant du Chalet, where they caught Gauguin’s eye, and he asked to swap one of his landscapes for the pair.

This exchange was the trigger for the disastrous couple of months the two artists spent working together in Arles, ending with Van Gogh’s ear incident, after which Gauguin fled precipitately back to Paris. Bailey skewers him for his lack of feeling both at that point, and after Van Gogh’s death; although the latter must have been incredibly tricky to live and work with, Gauguin’s coldness on his suicide (in 1890), and his active hostility towards Emile Bernard’s posthumous exhibitions of Van Gogh’s work, are striking. By 1895 Gauguin was selling what he owned of his friend’s pictures; the two sunflower paintings went to the dealer Ambroise Vollard. The documentation of Two cut sunflowers reveals that Gauguin wrote in February 1895 to Charles Dosburg, the framemaker, asking him to collect both sunflower pictures from Vollard, presumably to frame them appropriately for sale. They would probably still have been in their first frames: until now we have had only one original Van Gogh frame for information about these.

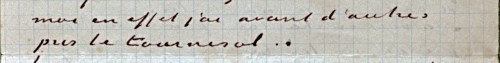

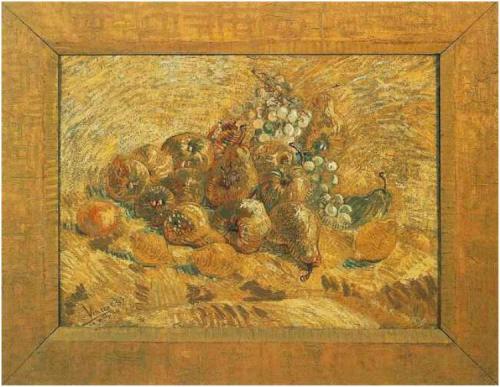

Van Gogh, Quinces, lemons, pears and grapes, 1887, Van Gogh Museum. Photo by Michelangelo5.

Quinces, lemons, pears and grapes was painted in Paris, in Theo’s flat. It is not included in The sunflowers are mine, for obvious reasons; however, this still life has affinities with the large sunflower paintings produced in Arles, as it is a study almost completely executed in shades of yellow. The frame is the simplest of profiles – a flat frieze, with a canted sight edge – the whole painted in a basketwork pattern of lemon yellow on yellow ochre. At first, however, the sight edge was apparently painted red, rather like the inner edge of the integral painted border on The bridge (after Hiroshige). In the case of the latter, the red edge was a complementary foil to the greens of the decorative border and the painted sea; with the still life, the red edge creates a strangely uncomfortable effect, simultaneously flattening the whole work into a tapestry-like plane, whilst focusing claustrophobically on the arrangement of fruit, as if through a window. The corner of the painting and frame, with the red sight edge, can be seen in the study for the portrait of Père Tanguy .

Van Gogh, Quinces, lemons, pears and grapes, with mock-up of the original red sight edge

However, the story of painting and frame is more complicated than an experiment with a border that was painted out. This still life was painted on top of an earlier work – possibly a landscape, with a green ground,

…found in the lowest paint layers and at the edges… there are traces of paint of exactly the same colour on the inner edge of the rebate, where the canvas came into contact with the wood while it was still wet.[1]

The red edge would have acted as a foil to a green painting, just as with The bridge, and at that point the main frieze of the frame was coloured a flat ochre, with no brushwork pattern. Van Gogh re-used canvases from time to time when he was particularly pressed for money, and he evidently inserted the old canvas with the new still life into the frame prepared for the first image. Frame and still life stayed like this long enough to feature in the study of Père Tanguy, until Van Gogh realized that he had to fit the one more harmoniously to the other, and painted over the red sight with a yellow related to the tints of the still life.

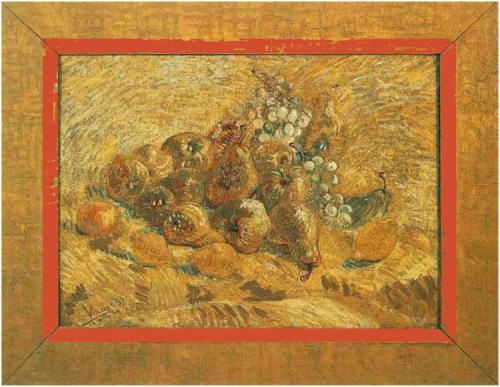

Detail of the sight edge on the right-hand rail of Quinces, lemons, pears and grapes, showing vestiges of the original red paint beneath the yellow. Photo by Holger Nordmann

He then worked over the whole surface with a brushwork pattern in lemon yellow, giving it an effect of shimmering movement as the impasto catches the light. The whole process gives a fascinating insight into his method of producing a complete artwork, in which the frame and painting would be in total harmony.

Van Gogh, Two cut sunflowers, 1887, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1949 (49.41). Photo by Alexis Tanukik

Other canvases have traces of paint round the edge, indicating that

the picture was placed in a frame that had been painted… but had not yet dried’ [2];

they include Alexander Reid, 1887, Kelvingrove, and Undergrowth with flowers, 1887, private collection. Two cut sunflowers, which was from the same year and had been prepared for exhibition, would almost certainly have been framed in a similar way, probably in an orange frame complementary to the blue background, making it even more likely to catch Gauguin’s attention in the exhibition. The 17th century Italian Baroque bolection frame which now contains it is an example of what has been for the last thirty years or so contemporary thinking on how to frame Post-Impressionist work by Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne – just as Picasso’s paintings are now often set in antique Baroque Spanish frames. This is based on an aesthetic choice: the age-softened chunky carving, the gentle ogee, hollow and convex profiles, and the deep, muted gilding through which the bole shows, all act as harmonizing support for the colouring, forms and brushwork of these particular artists.

Vincent Van Gogh, Four sunflowers gone to seed, 1887, Collection Kröller Müller-Museum, Otterlo. Frame designed byJac. van den Bosch, c.1910. Photo by Bertknot

The fourth of the four seed-head paintings was bought by Mrs Hélène Kröller-Müller in 1908, almost certainly in a dealer’s frame. She chose the collector’s route to framing, and, wanting an individual design in order to impose something of her mark on what was a very large collection of contemporary art, chose the Dutch interior designer, Jac. van den Bosch (1868-1948) to create a suitable pattern. The pale wooden frame of Four cut sunflowers is an example of his design. It has the advantage of simplicity and of being well-made; also of playing quite wittily with traditional forms of the frame in its subversion of the outset corner; however, the pinkish colouring of beech wood is perhaps not what Van Gogh would have chosen to bring out his gold and blue painting. Something like the creamily golden shades of boxwood would have been more in line with his strict opposition of complementaries, quoted by Martin Bailey (above).

The large vases of sunflowers which Van Gogh painted in Provence turn out to have been precipitated by a conjunction of events: ‘the flowers were at their best’: a mistral got up and he couldn’t paint outside: he heard just after he had started working on them that Gauguin was indeed coming to Arles: Gauguin’s childhood had been spent in Peru, ‘where legend associated sunflowers with the Inca sun god’. They may also have carried the symbolism of the love of God, deeply familiar to the ex-preacher Van Gogh, and perhaps symbolic for the community of artists he hoped to create in the south. Surprisingly, the only resonance not mentioned in the book is the traditional connection of the artist with the sunflower – the flower of Apollo. Van Gogh, who knew his Van Dyck, would almost certainly have been aware, probably through engravings, of this image:

After Van Dyck, Self-portrait with sunflower, c.1630, Courtesy of Philip Mould

Van Dyck, looking like a more cheerful version of Gauguin, and with a gigantic sunflower gazing at him adoringly, is a perfect symbol of Van Gogh’s hectic week in Arles, preparing for Gauguin an epic reworking of the two small sunflower paintings already in his friend’s possession.

Van Gogh wrote to Emile Bernard, Theo and his sister Wil, just after starting work: he described his plan of a ‘décoration’ for his studio of a number of sunflower paintings. Once he had begun them, they were completed extraordinarily quickly: Bailey has discovered that the four original works were finished in less than a week. This is really extremely fast: Van Gogh was deeply engaged with the subject and with fulfilling his purpose. It was an epic of long hours and quantities of expensive paint. Martin Bailey quotes Van Gogh:

‘I work on it all these mornings, from sunrise. Because the flowers wilt quickly and it’s a matter of doing the whole thing in one go.’

Three Sunflowers, 1888, Private Collection

He started with Three sunflowers (in a private collection and not exhibited for years, its frame never seems to have been published). Bailey notes the ‘dramatic change from his Parisian flower still lifes’: he is not now an Impressionist, following in Monet’s wake; he is a Post-Impressionist – he has become the Van Gogh with whom we’re all familiar.

Six Sunflowers, 1888, destroyed in WWII; reproduced from a photo, published 1921 in Tokyo. Courtesy of Mushakoji Saneatsu Memorial Museum

The second painting, of six sunflowers, carries the brilliancy of colour in the first into a new jewel-like burst of complementaries – royal-blue and orange, purple and yellow. Van Gogh’s love of golden shades was accompanied fittingly by an enthusiasm for royal-blue: in April 1888, he had written to Theo about a picture he was considering painting: (The Langlois Bridge, 1888, private collection)

Letter from Van Gogh to Theo, c. 3 April1888, Van Gogh Museum

‘…the drawbridge with a little yellow carriage and group of washerwomen, a study in which the fields are a bright orange, the grass very green, the sky and the water blue.

It just needs a frame designed specially for it, in royal blue and gold like this [sketch], the flat part blue, the outer strip gold. If necessary, the frame can be of blue plush, but it would be better to paint it…’[3]

He even added a band of blue around the painting, at the edge of the canvas, to try out this effect; it was not part of the painting, so was then bent round the edge of the stretcher [4].

The painting of Six sunflowers carries on this use of complementaries in the frame: Martin Bailey has unearthed an art print (the reproduction of Six sunflowers, above), made in Japan in the 1920s, which shows for the first time the original painted frame (or part of it). Van Gogh mentions the frames he and Gauguin were making in another letter to Theo of 10 November 1888:

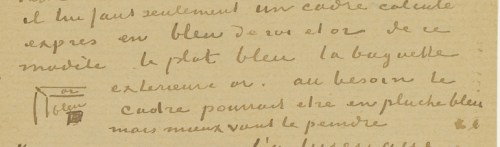

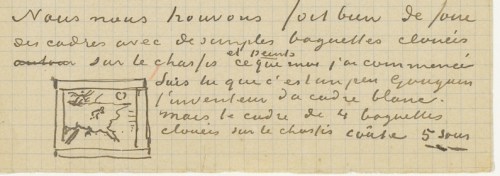

Letter from Van Gogh to Theo, 10 November1888, Van Gogh Museum

‘We’re very satisfied with making frames with simple strips of wood nailed on the stretching frame and painted, which I’ve started doing. [sketch]

Do you know that Gauguin is partly the inventor of the white frame? But the frame made from four strips of wood nailed on the stretching frame costs 5 sous, and we’re certainly going to perfect it. It serves very well, since this frame doesn’t stick out at all and is one with the canvas…’

It is a huge coup on Martin Bailey’s part to have found a reproduction of one of these frames – and such a vivid image: the colours given to the areas of the frame which lie by the royal blue background or the lavender table-top are clearly differentiated into orange and gold, as Van Gogh copies Seurat’s modulation of his painted borders and frames against the paintings they contain. This particular sunflower painting was sold by Theo’s wife in 1908, eventually being bought in 1920 by Koyata Yamamoto, who took it to Tokyo. It had been framed between 1908 and 1920 in a Louis XIV gilt frame, after the fashion for Impressionist paintings, and Bailey has found, in the same Japanese museum which owns the colour photo of the Six sunflowers, a black-&-white photo of its new owner sitting beneath it. The original painted frame is still visible at the sight edge of the gilt frame, fractionally more of it than in the colour print, whilst even more must be concealed under the rabbet of the gilt frame. A width of probably twice what we now see in the reproduction would make sense, given Van Gogh’s little sketches of his and Gauguin’s frames, and the fact that he calls these ‘baguette’ frames. The outer gilded setting was in the end what did for this sunflower picture: it perished in an American bombing raid in 1945, the frame too heavy for it to be saved.

Fourteen sunflowers, 1888, Neue Pinakothek, Munich. Photo by Oliver Kurmis

The other two sunflower paintings have long been divorced from their painted ‘baguette’ frames. The third in the series, Fourteen sunflowers, would presumably have had an reddish-orange border around the top and two-thirds of the sides, and purple against the yellow table at the bottom. It’s now set in a 17th century Italian reverse frame, similar in profile to the one on Two cut sunflowers in the Met, above – but this one has a delicate and appropriate punchwork pattern of undulating leaves and flowers on the frieze, bordered by chunky mouldings which reflect the brushwork and the strong compositional elements of the painting.

Vincent van Gogh, Fifteen sunflowers, 1888, © The National Gallery, London

The last and largest of the series, Fifteen sunflowers, would by the same analogy have had a frame painted in shades of purple. Now its intense yellows are no longer what they once were, and it fits equably into its ‘new’ frame (actually an early 17th century Italian painted and silvered cassetta frame, with a small inner slip). When fresh from the artist’s hand, however, the complete set of four sunflower paintings would have produced an extremely vibrant effect in their variously coloured frames; the last two large ones were placed together on Gauguin’s white bedroom wall.

Approximation of sunflowers hanging in Gauguin’s bedroom in Arles, with its walnut furniture

Also in Gauguin’s room were ‘four landscapes of the Place Lamartine, which he called “the poet’s garden”’, which were basically green paintings, probably bordered in red. Van Gogh’s sense of colour in a hang of paintings is treated in the Van Gogh Museum Journal 1999 – scroll down to fig. 2 & ff. for the sixth Les Vingt exhibition early in 1890.

The attempt to forge an artistic community, beginning with Gauguin, imploded after only two months. Bailey has, extremely cleverly, worked out the trigger of the ear incident, from evidence in another still life painting. Gauguin fled… although a few weeks later he was apparently trying to wangle a copy of Fifteen sunflowers in another exchange of paintings. Van Gogh decided to copy both it and Fourteen sunflowers; another copy (unsigned) of Fifteen sunflowers was also made.

Signed copies (1889) of Fourteen sunflowers, Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Mr and Mrs Carroll S. Tyson, Jr, Collection; Photo Geronimo the Elder; & Fifteen Sunflowers, Van Gogh Museum; Photo by Michele Ahin

Unsigned copy (1888-89) of Fifteen sunflowers, Seiji Togo Memorial Sompo Japan Museum of Art, Tokyo; Photo Bunny Chan

With images of all these various sunflowers assembled together, it’s extremely interesting to see how the wheel of time has turned for Van Gogh, as instanced by the style of his frames. The artist who was once unable to sell his work, save for two or three paintings, is now considered of such worth that a great deal of money is lavished on framing his pictures. The Neue Pinakothek, National Gallery and Van Gogh Museum have all opted for Italian cassetta frames, simple in form but rare and beautiful; the Metropolitan Museum has gone for a Baroque version of the same style; the Kröller-Müller Museum has kept its patron’s specially-designed 20th century wooden frame, just as the Philadelphia Museum has retained the dealer’s grand and opulent Louis XV pattern. It is perhaps surprising that the Sompo Japan Museum hasn’t taken the step of reframing its sunflower painting; Van Gogh’s original slender painted frames are closer to a Japanese aesthetic than is the current frame. Bailey illustrates this version of Fifteen sunflowers (unsigned copy) in the frame it wore in 1915; it was a much more suitable chunky Italian Baroque bolection frame.

Van Gogh moved back to Paris, and then to Auvers-sur-Oise, into the care of Dr Paul Gachet, in May 1890. His last painting has, since last year, been thought to be Tree roots, in the Van Gogh Museum , but Bailey reveals it to be Farms near Auvers (‘Village [derniere esquisse]’), in the National Gallery, London. There are four sunflower plants in the foreground of the latter, blooming along the fence around the farmhouses.

After his suicide, the book moves to a consideration of what happened afterwards to Van Gogh’s sunflowers – their buyers, exhibitions, and where they hung; also to other painted sunflowers. Some of these were Gauguin’s, who does not emerge at all well from this book, trying to edge Van Gogh’s work out of exhibitions, to emphasize his madness, and to imply that he, Gauguin, had suggested the motif of sunflowers, and the use of a lot of intense yellow. He ended up – in a macabre echo of his dead friend’s work – by producing four pictures sunflowers for the dealer, Ambroise Vollard, in order to support himself in Tahiti; Bailey illustrates all of these.

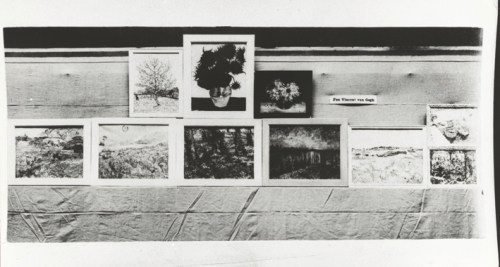

Van Gogh’s sunflowers moved through many collections after his death; the National Gallery painting remained with Theo’s wife, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, and still appears to have been the property of her and her son when exhibited in Cologne in 1912. It is shown in a wide white architrave frame, perfectly flat, which seems to have been the default solution during the later 19th and early 20th century for Van Gogh’s work (at least, where dealers had not got hold of it and stuffed it into antique Louis XIV or XV frames).

In a letter of 18 September, before Gauguin arrived in Arles, Van Gogh’s discussion of frames with Theo had specified ‘light walnut’ and ‘heavy oak’, at 5 francs a go. On 16 October, he mentions a white frame for the painting of his bedroom; then, after Gauguin’s arrival, and when the two artists had started to make coloured strip frames, the letter (quoted above, 10 November 1888) which describes this also notes Gauguin as ‘partly the inventor of the white frame’. The white frame had, in fact, a history of use by other avant-garde painters such as Degas and Pissarro, as well as Gauguin; after Van Gogh himself began to use it (for instance, for the 1890 exhibition of Les XX), Theo seems to have accepted it as the most appropriate, au courant and simplest way to display his brother’s work. It was also cheap: these flat, white architrave frames were probably made by Père Tanguy for 10 francs each. Sometimes they were applied around the existing coloured edging, where that had been added, but usually they were employed alone. After Theo died in 1891, the interiors of Jo van Gogh-Bonger’s house in Amsterdam show Van Gogh’s paintings hanging in these very plain white frames (the odd one is in a gilded moulding). Given that there were 400 or so paintings in the family collection, only 55 of which had already been framed whilst the brothers were alive, this solution was in many senses one of the best [5].

Fourteen sunflowers and other works by Van Gogh at the Association pour l’Art exhibition in Antwerp, 1892. Photo: Van Gogh Museum

The Dutch Ambassador opening London’s first major exhibition of Van Gogh’s work in 1947 (The Times; with thanks to Rob Lordan)

The 20th century, however, saw the gradual erosion of these frames which had had at least some connection with the way in which Van Gogh himself wanted to present his paintings. Bailey has assembled an interesting collection of later frames applied by dealers and collectors; these supplement the photos in Van Tilborgh’s essay in In perfect harmony. One of the most interesting and exotic of subsequent reframings is the pattern designed in 1925 by the French Art Deco designer Pierre Legrain for the couturier and collector Jacques Doucet.

Manet, On the beach, 1873, Musée d’Orsay; frame by Pierre Legrain

We know Legrain’s style of frame from that still on Manet’s On the beach in the Musée d’Orsay; the companion frame for Van Gogh’s Irises (1889, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), is now in the Fondation Angladon-Dubrujead, Hôtel Massilian, Avignon, donated by Jacques Doucet’s heirs. Bailey describes it as ‘a dramatic frame in black lacquer, decorated with irregular, large golden discs’. Van Gogh might have liked the complementary gold of the discs for his purple irises, whilst possibly preferring the red lacquer of the Manet frame as a foil for the green of their leaves. The latter frame has a very austere structure, which he would have approved; and although the sophistication of an Art Deco pattern is superficially a long way from the simplicity of his original frames, this particular design is not unlike the decorative painted borders of his ‘Japanese’ images.

Bailey’s book is a readable, revealing work on an artist we may think has little left unknown about his life. But The sunflowers are mine uses an effective and imaginative focus to view his work; by concentrating on his most popular subject this focus is tighter, cutting out most of the earlier, bleaker years, and illuminating the pivotal weeks he prepared for and lived with Gauguin in Arles. Bailey has also made some interesting discoveries, and has included helpful and fascinating information on the frames of Van Gogh’s work, and on the subsequent careers of the sunflower paintings. It is rare as it is satisfying to find a book like this, which considers the whole work of art – the painting and the frame.

***********************************************************

Note that two of the five large sunflower paintings will be exhibited together at the National Gallery, London, from 25 January – 27 April 2014

Banksy, Sunflower from a petrol station, exh. Crude Oils, Notting Hill, 2005

[1] Louis van Tilborgh, ‘Framing Van Gogh: 1880-1990’, In perfect harmony: Picture + frame 1850-1920, ed. Eva Mendgen, 1995, p.164. This study notes the number of canvases by Van Gogh which had red borders painted around the edge of the canvas, and which would, van Tilborgh believes, have been given white frames, as in the integral painted white and red border to Still life with coffee-pot, 1888, Private collection, .

[2] Ibid.

[3] Van Gogh Letters, no. 592, c. Tuesday 3 April 1888, Van Gogh to Theo.

[4] Van Tilborgh, op.cit., p.168.

[5] Ibid., p.170 & 174.

With thanks, once more, to all the museums who have allowed me to use images from their collections, and to the photographers who share their work on the internet.

I’ve found an old framed Sunflowers paiting. I do not think it it’s an original but this painting is very old. The frame seems to have been built around the photo. It was left in a house in Illinois then all contents of the home where donated to a missionary group who drops the items off at different thrift stores throughout several states. I bought the painting in MS. I have done hours and hours of research for the past month and have not had any luck. Would you be willing to look at my photos of this painting?

Look forward to hearing back

Mary

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment. Sadly, I’m not an expert on Van Gogh; the best thing to do would be to take it to your local museum or public art gallery, and ask the curator of 19th/20th century paintings to have a look at it. Good Luck!

LikeLike

I read this recently and completely agree with your summary. I loved the pictures of various versions in private homes too. Chester Beatty had a horrid room, but such amazing art on the walls (two Seurats as well as Sunflowers).

LikeLike

Thank you Michael; am so glad that you approve. I thought the interior shots were one of the great pluses – even Mirbeau’s dining-room! – which was a bit of a coup. And I quite agree as to Baroda House… none of the paintings look at all comfortable in their setting.

Really liked your review of the Haskell, by the way… has gone onto Christmas list!

LikeLike

Dear Lynn, Great to see all those frames around Van Gogh’s sunflowerpaintings! Thank you so much for sending frames news into the world! Also thanks for endorsing me. Greetings, Gini

LikeLike

Dear Gini –

Thank you for such a nice comment – and for helping me to get one of the images! I should be completely stuck without people like you!

Best wishes, Lynn

LikeLike