Jacques-Louis David’s frames: Revolution, Empire and beyond

David’s career lasted from the beginnings of NeoClassicism in France in the 1760s until his death in 1825, four years after that of his hero, Napoleon, and a decade after the end of the French Empire in the mud and blood of Waterloo.

His education in art began on the cusp of the change from Rococo to classicism; he was taught initially by Boucher, which enabled him to take over from Fragonard in one of his first commissions, aged 25, to produce a set of four painted panels for the salon of the dancer, Mademoiselle Guimard. The surviving panel – a Portrait of Mlle Guimard as Terpsichore – is in full and surprising Rococo style, given how David’s career was to evolve. His subsequent and seminal development of NeoClassicism was helped by the publication in the 1750s of illustrated works on the archaeological excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, and by a visit to both sites by the Marquis de Marigny, brother of Madame de Pompadour and from 1751 the director of the Bâtiments du Roi. The reign of Louis XVI from 1774 was the reign of fully-fledged NeoClassicism, and it was also the period when David, born in 1748, having grown from a student under Joseph-Marie Vien to the winner of the Prix de Rome, travelled with Vien in 1775 to the Academie française in Rome.

David (1748-1825), Madame François Buron, 1769, o/c, 66.3 x 55.5 cm., in Louis XVI frame of 1775 onwards, Art Institute of Chicago

His expressive portrait of his aunt, Mme Buron, painted in 1769 when he was still a student at the Académie royale in Paris, has been fitted out (by use of an inlay at the sight edge) with a frame of the mid-1770s, when the fully-realized Louis XVI NeoClassical style was percolating into general use [1]. It has a strictly rectilinear structure, enriched with parallel bands of ornament based closely on decoration copied from antique ruins, which had been diffused by, amongst others, enthusiastic students at the Académie français in Rome.

Montage with David, Mme François Buron, 1769, in transitional frame of 1765 onwards

It might more accurately have been given a transitional frame, had one been available – designs which bridged the gap between the asymmetrical curvaceousness of high Rococo and Louis XVI style, with its adoption of classical, architectural ornament on a symmetrical form. This imaginary reframing would provide David’s work with a full complement of NeoClassical styles, from their birth in his adolescence to the end of the first Empire.

David in Rome

Having been awarded the Prix de Rome after four attempts and one hunger-strike, David spent five years there – until 1780 – on an extended scholarship.

David (1748-1825), Roman sketchbook, 1770s, Album 11, Getty Research Institute

David (1748-1825), studies of the antique from Album of drawings 3, folio 9, Department of Prints & Drawings, Musée du Louvre; RF 9136 10

His sketchbooks from the 1770s and -80s are stuffed with drawings of classical bits and bobs: urns, thrones, vases, sarcophagi, tripods, swords, helmets and carved ornament; these clearly began, first to train his mind and his eye, and then as a means of accurately depicting interiors, backgrounds and props for his paintings; but, with Napoleon’s rise and the eventual need for a national decorative style which would replace the idiom of the ancien régime, they became part of the library of references which would help to develop the ornamental language of the Directorate and Empire.

David (1748-1825), collection of sacrificial objects from Album of drawings 9, folio 17, Department of Prints & Drawings, Musée du Louvre; INV 26117.C, recto

Johann Winckelmann (1717-68), Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums, 1764, Dresden

Once in Rome, David was introduced to the ideas of Johann Winckelmann by the latter’s close friend and collaborator, the artist Anton Mengs, who in 1762 had himself written a treatise on the influence of the antique on art [2]. Two years later, Winckelmann had published his seminal history of art in ancient Greece and Rome; a book which influenced the way in which antique works of art were perceived in the later 18th century, and continued to do so well into the 20th century [3]. As Thomas Pelzel summarizes Winckelmann’s thesis, he thought that,

‘Greek art is not only more aesthetic, it is also more noble and moral than modern art, the fruit of a culture more noble than the post-classical world. The concept of art as inherently linked to social structure and morality intoxicated the 18th century imagination’. [4]

Although Winckelmann had died in 1768, several years before David reached Rome, Mengs was still living there, and – if his own work was (like the transitional frame) only midway along the road between the Baroque and NeoClassicism – his ideas were fully in tune with Winckelmann’s, and stimulating for a young painter who had experienced a revelation before the ruins of Herculaneum and the treasures of Pompeii.

Anton Mengs (1728-79), cast collection: top left: coloured etching of Mengs’s cast collection installed in Johanneum, Dresden, 1st half 19th century; top right: head of Zeus or Asclepius; bottom left: fragment of acanthus frieze; cast collection in Dresden in 2016: photo: SchiDD

Mengs had also collected a large number of plaster casts of antique sculpture, which he opened as a teaching collection for artists, and which later formed important parts of the classical collections in two European museums [5]. As can be seen in the images of the installation, the collection contained – besides complete statues – busts, vases, and panels of ornament.

David (1748-1825), right: a view of Mengs’s cast collection in Dresden, with sitting dog; left: study of sitting dog from Album of drawings 10, folio 15, Department of Prints & Drawings, Musée du Louvre; INV 2660.C, recto

David’s familiarity with this collection is found in the albums of drawings (more than a thousand) that he made in Rome, and which informed all his subsequent paintings of classical scenes.

The head of Zeus or Asclepius in Mengs’s cast collection; David (1748-1825), The wrath of Achilles, 1819, detail of the head of Agamemnon, Kimbell Art Museum

His continued use of them throughout his life can be seen, for example, in his 1819 painting, The wrath of Achilles, where the head of Agamemnon clearly refers to a drawing – which David must have made forty years earlier – of the head of Zeus, one of Mengs’s casts. Eventually his frames would also be decorated after the antique, and almost certainly using drawings which he had made in Rome, either in front of Mengs’s cast collection or directly from friezes and panels of classical ornament from the architectural fragments which still filled the city.

David (1748-1825), The funeral games of Patroclus, 1778, o/c, 94 x 218 cm., NG of Ireland

Many of David’s earlier paintings have been reframed in the light of later works, making it difficult to understand exactly when his own choices or designs began to be used. For example, his panoramic scene of a furious Achilles piling sacrificial victims on Patroclus’s funeral pyre may possibly have been framed like this for its first exhibition in the Académie française in Rome in 1778, the year it was painted, or when David brought it back with him to France, and submitted it to the Salon of 1781: the frame has similarities with contemporary fashion, and might perhaps be the original – although the wide ¼-round concave moulding is closer to Restauration frames, and may equally well date from the Bourbon monarchy, post-1815. It is not in any case David’s design, but is one of the stream of NeoClassical and NeoClassical revival patterns employed from the 1760s until the end of the 19th century, or later; simple and versatile, like the plain forms of the Baroque Roman ‘Salvator Rosa’ frame, which has also endured for a remarkably long time.

It may not be his invention; it may have been employed by a later collector, possibly even after the artist’s death; but it manages to summarize much of what David had learnt in Rome, symbolizes his movement away from the last vestiges of the Rococo, and expresses his emergence into full NeoClassical style. Compared with the ornamental structure and decoration of Rococo and Transitional patterns, it is very minimalist – a deep, plain scotia and narrow frieze, with a small guilloche at the top edge, a run of beading, and rais-de-coeur at the sight edge.

David (1748-1825), Belisarius begging for alms, 1781, o/c, 288 x 312 cm., and details, Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille https://pba.lille.fr/Collections/Chefs-d-OEuvre/Peintures-XVI-sup-e-sup-XXI-sup-e-sup-siecles/Belisaire-demandant-l-aumone/(plus)

The first version of the blind Belisarius begging for alms may possibly retain its original plain, NeoClassical frame, with two hollows separated by a small fillet and two runs of very small decorative mouldings, or may be a later collector’s frame Its simplicity suits the very large size of the painting, and the parallel lines of the concave mouldings and fillets echo the fluted columns, and emphasis the long recession of space to the distant hills beyond. Like The funeral games of Patroclus, this work was shown at the 1781 Salon.

David and royal patronage

For most of the 18th century, the home of the French royal family had been in Versailles, rather than in the extensive buildings of the Palais du Louvre and the Tuileries. The latter was used mainly for its theatre, whilst the Louvre became a maze of apartments for civil servants, artists, and craftsmen working for the Bâtiments du roi.

‘Around 1750, craftsmen, artists, and suppliers involved in restoration were mainly grouped in the Louvre quarter, which housed a dense and concentrated network of dealers’ shops and workshops of painters…’ [6]

The appearance of his work in the 1781 Salon brought David to the attention of Louis XVI, and he was granted one of the grace-and favour apartments in the Louvre, which allowed him to marry. The supervisor of the Bâtiments du roi, Charles-Pierre Pécoul, had a daughter who became Madame David, bringing with her the financial security of a government official’s family; this allowed David to set up his own studio, and begin to teach. His connection to Pécoul, and proximity to the other artists and craftsmen living in the Louvre, may also have given him better access to the carvers, répareurs and gilders, who, at the top of their profession, made frames for the king and the court. Many of them lived and worked in the streets around and beyond the Bastille (rue de Charonne, rue Saint-Antoine, rue de Melai, Meslée or Meslay, rue de Lappe and rue de la Roquette), but would have frequented the Louvre to make deliveries and consult the artists and officials of the Bâtiments du roi.

David (1748-1825), The oath of the Horatii, 1784, o/c, 303 x 425 cm., Musée du Louvre

David took his wife and some of his students briefly back to Rome in order to paint this declaration of republican virtues, above (which had been commissioned, ironically, by the king). As a royal commission it would probably have been given a relatively grand NeoClassical frame; it is now housed in a standard Louvre moulding, even though it has spent all its life in the Museum. Perhaps the putative grander design is lurking somewhere in the vastness of the basements.

David (1748-1825), Charles-Pierre Pécoul, 1784, o/c, 91.5 x 72.5 cm., Musée du Louvre

David (1748-1825), Madame Pécoul, o/c, 92.5 x 72 cm., Musée du Louvre (acquired by the state in 1844)

However, when he returned to Paris, his widowed father-in-law had remarried, and David painted his portrait together with a pendant of his new wife. These are almost certainly their original Louis XVI frames, although the frame of M. Pécoul seems slightly too tall for the canvas, revealing the stretcher at top and bottom.

Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), Comtesse de la Châtre, 1789, 45 x 34 1/2 in. (114.3 x 87.6 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art

David, Madame Pécoul, detail (top right), and Vigée Le Brun, Comtesse de la Châtre, detail (lower left)

But the pattern is an up-to-the-minute one; it is a plainer version of, for instance, the spectacular fronton frame on Vigée Le Brun’s portrait of the comtesse de la Châtre. It uses a NeoClassical profile which would appear frequently on David’s work, with a flat top edge, and a scotia and frieze separated by small architectural mouldings. The Vigée Le Brun frame is more refined, with a guilloche on the top edge, narrower fillets between the flutes, and a sharply defined run of pearls rather than the slightly chunkier beads on David’s frames; it also has an acanthus leaf-&-leaf tip at the sight edge, where the unadorned version has rais-de-coeur. The whole design, although appearing relatively simple and straightforward, is very sophisticated in its use of ornament: the fillets and flutes are alternately burnished and matte, the reflected and interrupted light creating a flicker of movement around the painting, and the curve of the scotia helping to throw this moving light onto the painting, animating it, and enhancing the realism of the subject. The inward-pointing fillets also emphasize the perspectival recession within the picture. These functions of the frame, its profile and its decoration are immediate but usually completely unrealized by the spectator, accounting for the popularity of fluted NeoClassical frames from the 1760s or 1770s until the early 20th century.

This seems to be one of the earliest survivals of the profile which the artist took with him through the next half a century – the same flat top edge, scotia and frieze, softened with motifs which he must have designed, but basically similar to the end of his career.

David (1748-1825), The death of Socrates, 1787, o/c, 129.5 x 192.2 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Interestingly, another example of the fluted hollow frame appears on The death of Socrates – one more large classical scene, almost 6 feet 6 across, which was exhibited in the 1787 Salon. Because of the size of the canvas, the moulding has been given importance with a decorated back edge (guilloche), piastres on the top edge, and an additional inner frieze. This frame is a product of the NeoClassical revival in the 19th century, with its very close-set flutes, large and rampant moulded acanthus corners, and the stepped frieze at the sight edge; but although it was made half a century later than David’s original frame, it helps to demonstrate the versatility of the fluted moulding, which to a large extent came to represent the NeoClassical style throughout the 19th century. The death of Socrates is a scene which brings the ancient world to life through its composition and use of gesture, derived from friezes of figures in sculptured reliefs and on sarcophagi, and backs this up with meticulously studied objects and furnishings. The frame – even though a retrospective addition – both supports this archaeological realism with its decorative mouldings, and, again, reinforces the deep spatial recession, from the brighter foreground to the small figure of Socrates’s wife on the distant stairs.

David (1748-1825), Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier et sa femme, 1788, o/c, Metropolitan Museum, New York

With his success in the 1781 Salon and the patronage of Louis XVI, David was sought after for private commissions and portraits, and in 1788 he was asked to paint a double portrait of Antoine-Laurent and Marie-Anne Lavoisier. They were an aristocratic couple, enriched by Lavoisier’s position as a tax collector, and David originally painted them in a different setting, with a gilt ormolu table and Madame in a fashionably tall, flowery and beribboned hat with a feather. He intended to show the work at the 1789 Salon, but the committee was wary of inflaming the simmering tensions in the populace by such an overt show of wealth. David painted out the hat, toned down the background, and added scientific instruments to emphasize Lavoisier’s work as a chemist (in which his wife helped), which included formulating the earliest table of elements and proving the existence of oxygen; Lavoisier also worked for the public good, studying ways of providing clean water to Paris and ventilating the hospital properly [7]. The amendments to the painting were not enough to prevent its exclusion from the Salon, however, and the painting remained in the family until the 1920s.

The extraordinarily splendid frame in which it is now displayed in the Metropolitan Museum was not another part of the initial rampant display of domestic life for the upper ten thousand, as might be thought. It’s a much later addition to the picture, and is actually – and ironically – a version of a royal frame designed and carved by François-Charles Buteux, sculpteur des bâtiments du roi, twelve of which were produced for state portraits of Louis XVI by Antoine-François Callet [8]. All of them include the royal impresa of three fleur-de-lys on a single or double cartouche at the top. This frame, now on the Lavoisiers, is closest to that of Callet’s Louis XVI in the vestibule of the Château Coppet, on the Lake of Geneva . David’s frame, or the Lavoisiers’ own choice, remained behind when the portrait was sold out of the family. It was presumably a much plainer affair (possibly another fluted scotia frame, like those on the Pécoul family portraits), in keeping with the artist’s efforts to tone down the general opulence of the whole work for exhibition; but sadly Lavoisier was still guillotined in 1794, a year after his king.

David as designer

Before he arrived at the point where he held the unofficial post of Artist to the Empire, David was already designing objects as well as painting them. The person he chose to interpret his furniture designs was the ébéniste or cabinetmaker, Georges Jacob, who had become a maître-menuisier (master carpenter) in 1765, and supplied the queen, the king’s brothers, the Dauphin, and many members of the French aristocracy . His fame also brought him commissions from Gustavus III, King of Sweden, and the Prince Regent in England. David’s studio in the Louvre, as well as his relationship to the supervisor of the Bâtiments du roi, would have introduced him more easily to a peer of equal prestige as himself, who also supplied the royal family, was similarly innovatory, and had the same interest and grounding in the forms and ornaments of the classical past as David. Jacob had also moved in 1775 to the rue Meslay (or Meslée, as he spelt it), where two of the great 18th century framemakers had had their workshops.

David (1748-1825), designer: table made by Georges Jacob (1739-1814), after a design by David, mahogany, gilt-bronze mounts, c.1785-89, 77 x 107 cm., Sotheby’s, 4 July 2012, Lot 28

David (1748-1825), designer: armchair made by Georges Jacob (1739-1814), after a model by David, mahogany, parcel-gilt and painted wood, ebony, wrought iron, c.1786-89, 81 x 66 x 70 cm., and detail, Marc-Arthur Kohn, Paris, 2 December 2013, Lot 24

This chair and table were made by Georges Jacob for David’s studio as props to furnish his classical compositions, in the style of the drawings he had made so exhaustively in Rome, and both appear in the painting below, which was shown in the Paris Salons of 1789 and 1791, and – like The oath of the Horatii – entered the collection of Louis XVI.

David (1748-1825), The lictors bringing the bodies of Brutus’s sons to him, 1789, o/c, 323 x 422 cm., and detail, Musée du Louvre; with Georges Jacob’s chair

The chair, without its ebony balls and painted feet, can be seen on the extreme right, where Brutus’s grief-stricken wife is leaping from it. Behind her, in the centre, is the table – although only its pedestal and feet can be seen beneath the cloth covering it.

David, The lictors bringing the bodies…, 1789, detail of Brutus’s chair (left); philosopher on a ‘klismos’ chair (detail), from Album of drawings 9, folio 5 recto, Department of Prints & Drawings, RF 9136 10; both works Musée du Louvre

Brutus is brooding at the left on another chair, a version of which was also produced for him by Jacob; it is clearly based on a drawing made by David in Rome of an extremely grumpy philosopher sitting on a chair with the same swoopingly curved legs. This is annotated at the bottom ‘à la villa negroni’ (the Villa Monalto-Negroni), but time, tide and various sales have taken their toll of the collections in the Villa, and the philosopher – having gone off to sulk in some unspecified location – cannot be included here.

One of David’s pupils, Etienne-Jean Delécluze (1781-1863), has left a memoir of his student days – written, weirdly, in the third person – in which he describes his first visit to the artist’s studio in the Louvre [9], when he saw the Georges Jacob furniture. This was in 1796, when he was fifteen-&-a-half (shades of Adrian Mole):

‘…But if the paintings attracted keen interest by their quality, the furniture of the studio was, in its way, no less diverting an object of curiosity. Up to this point, even the most opulent furniture in Paris was still made in the style of Louis XV or Marie-Antoinette, whilst in the studio of the Horatii it was to a completely different design. The upright chairs in sombre mahogany [Brutus’s chair], covered with cushions in red wool, with black palmettes along the seams, had been copied from the most common type on so-called Etruscan vases. Instead of the customary pair of armchairs, on one side there was an X-frame folding chair in bronze, where the bars of the X were finished with animal heads at the top and paws at the bottom, and on the other a large seat with a back in heavy mahogany, decorated with gilt-bronze mounts, with red and black cushions and draperies [Brutus’s wife’s chair]; everything had been faithfully copied from the antique, and executed by the most talented cabinetmaker of the period, Jacob, after designs by David and his student, Moreau…

…What is more, all these things, made to David’s design and commissioned by him, were, properly speaking, pieces of studio furniture, which the artist copied in his paintings….’ [10]

Delécluze goes on to note that furniture was not the only thing which was designed or decorated under David’s aegis:

‘It should not be forgotten that all this furniture had been made six or seven years before Etienne saw it for the first time in 1796. For the public, this taste only had to appear to begin to spread. Jacob’s furniture after the antique was spoken of as a novelty; Quinquet was perhaps less proud of the invention of his lamps [11] than David’s students of the Etruscan ornaments they painted on their frames…’ [12]

Like most of the Impressionists’ early coloured frames, none of these painted Revolutionary-era frames seems to have survived, rather sadly; presumably they contained the pictures which were kept in the artists’ lodgings or given to family and friends, whilst the ones submitted for exhibition or entered for things like the Prix de Rome would have had professional frames made for them by reputable carvers and gilders (see below for David’s frame-aware students).

Hubert Robert (1733-1808), designer: X-frame armchair made by Georges Jacob (1739-1814), after a drawing by Robert, 1787, mahogany, 96.5 x 64 x 71.1 cm., for Marie-Antoinette’s dairy at Rambouillet; now Petit Trianon, Versailles

At the same time that David was commissioning furniture in a replica Roman style from Jacob, his fellow artist Hubert Robert was ordering his own classical designs from the same maker on behalf of the queen. This is interesting, not only because of the simultaneous nature of the orders (did one artist influence the other?, and, if so, which and which?), and their widely differing functions (fairly historically accurate studio props for a radical artist, and slightly romanticized accoutrements for a rôle-playing queen), but for the way in which the ornaments used fed into the evolving look of the NeoClassical frame.

It is difficult to find a classical prototype for Hubert Robert’s chair (which is labelled ‘Etruscan style’) analogous to, for instance, David’s klismos chair. The X-shaped struts at the back and on the seat are rather strange, and may even be a misreading of the cords threaded through the canvas supports for upholstery in Renaissance versions of the X-frame chair.

Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), Hubert Robert, 1788, o/c, 105 x 84 cm., and details; with double scotia, decorated below the top edge with alternating anthemia and oak leaves; undulating branches of bay leaves-&-berries; rais-de-coeur at the sight edge; Musée du Louvre

Vigée Le Brun, Hubert Robert, 1788, detail of frame; Georges Jacob & Hubert Robert, X-frame armchair, 1787, detail

However, the band of pierced anthemia along the back, which is repeated as a moulded ornament in the hollow of the frame on Hubert Robert’s own portrait by Vigée Le Brun, became one of the hallmarks of the Directoire and Empire styles, and adorns a great number of David’s frames. It is tempting to think that the origins of this ornament may have been here, in this trio of men who were using the continually increasing contemporary knowledge of the classical world to remake the NeoClassicism of the previous twenty years.

Louise-Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), Mme Vigée Le Brun et sa fille Jeanne-Lucie-Louise dite Julie, 1786, o/c, 105 x 84 cm., Musée du Louvre

Was it, however, the original frame for the portrait of Hubert Robert? Exactly the same ornamental moulding frames Vigée Le Brun’s self-portrait with her daughter, painted in 1786, which has the same provenance as the portrait of Robert [13]. Both pictures were bought before the Revolution by Jean-Joseph, marquis de La Borde, were later seized and entered on the list of art and antiquities belonging to those who had fled or been executed, found their way back in 1800, after the Revolution, to La Borde’s family and then to the artist herself, and were given to the Louvre in 1843 by Vigée Le Brun’s niece. It is probable that they were framed together after 1800, when they were back with La Borde’s widow or son, or when they came back to Vigée Le Brun herself in the 1830s.

David (1748-1825), The courtship of Paris and Helen, 1788, o/c, 146 x 181 cm., Musée du Louvre

On the other hand, in 1788, the same year that Vigée Le Brun was painting Hubert Robert, David was commissioned by the comte d’Artois, younger brother of Louis XVI, to paint Les amours de Pâris et d’Hélène. The painting is also tagged ‘saisie révolutionnaire’ on the website of the Louvre, which indicates that it must have been finished and delivered to the comte before the upheavals of 1789, and also, therefore, probably framed; however, as the comte managed to survive long enough to be crowned Charles X in the Restauration, and as the picture only entered the Museum officially in 1823, it may have been given back to him on his accession. Does this mean that it is still in David’s original frame? or is its current frame more likely to date from the period when the painting passed through the ownership of the Convention, Consulate and Empire? In the latter case, David may have taken it into his own hands to frame it, sometime in the 1790s. Or was it reframed during the Restauration by its once and future owner, whose feelings towards David must have been ambivalent, to say the least ?

David: Revolution, Directorate and Consulate

David (1748-1825), Serment de Jeu de Paume, le 20 juin 1789 (The oath of the tennis court), after 1791, o/c, 65 x 88.7 cm., Musée Carnavalet

Everything fell apart during the Revolution – even in such apparently apolitical concerns as cabinetmaking, carving and gilding. Georges Jacob, for instance, came under suspicion because he had supplied furniture to the royal family and the court, but fortunately David’s patronage protected him from imprisonment. There were practical consequences which could be less easily circumvented; the swathes cut through the upper classes by flight and the guillotine removed a large number of purchasing clients from the books of the craftsmen engaged in the luxury trades. Records, also, must have suffered: especially amongst the percentage of suppliers who were unable to survive this loss of their clients, and through the removal of customers who were no longer there to pay for completed works.

Georges Jacob (1739-1814), one of a suite of six chairs & four armchairs, made between 1789- 94, mahogany (the leather seat is a modern extrapolation), stamped ‘G*IACOB’, Mobilier national de France. Photo: Isabelle Bideau

Many cabinetmakers, carvers and framemakers were left without customers, and once again Jacob only survived with David’s help, finding himself producing furniture for the Revolutionary National Convention. This suite originally comprised ten upright and ten armchairs, which by November 1795 were the property of the Garde-Meuble de la Convention nationale, which had replaced the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne. The Convention sent them to the Palais du Luxembourg, as part of the furnishings to accommodate the committee of the Directoire, the government of France between the monarchy of Louis XVI and the Napoleonic Consulate and Empire (1795-99). As official government furniture for a post-royal age, they offered a fairly restrained counterpart to the chairs Jacob had produced for the court and royal family; they look like the offspring of an English upright Hepplewhite chair and David’s klismos. Here a similar band of pierced and carved anthemia as on Hubert Robert’s Marie Antoinette chairs provides the main decorative feature (apart from the morphing lions), and indicates that this motif, with its related palmette cousin, is on its way to becoming one of the more important ornaments of the Empire style – especially on frames.

François-Joseph Bélanger (1744-1818), interior of the Hôtel de Bourienne, Hauteville, Paris, pre-and post- its recent restoration

It certainly featured in the decoration of the Hôtel de Bourienne, which was built in the Directoire style from 1787 into the early 1790s, and where the doorcases in the salon and the mouldings at the top of the ceiling-cove include friezes of anthemia and palmettes.

David (1748-1825), Madame de Pastoret & her son, 1791-92, o/c, 129.8 x 96.6 cm., and detail, Art Institute of Chicago

It also features on the frame of David’s unfinished portrait of Madame de Pastoret and her sleeping baby son. If not The courtship of Paris and Helen, might this be the earliest example of his characteristic frame? – the double hollow, the upper with a slight ogee to it and the lower a smooth sweep of gently reflecting gold; the flat top edge, and the other defining fillets bordered with pearls in the centre, and rais-de-coeur at the sight edge; the main moulding of alternating palmettes and lotus buds. Because Mme de Pastoret was a supporter of the king, and was imprisoned in 1792 (but later released), and because David was a radical and a friend of Robespierre, their brief coinciding for this portrait, as far as it went, ended before the painting was finished; the sitter refused to accept it and it stayed in the artist’s studio until bought after his death by her son [14]. If David had ordered the frame, as many artists tended to do, whilst the work was still in progress, then this probably dates it, and perhaps this pattern, to 1791. Etienne-Jean Delécluze’s memory of seeing Georges Jacob’s ‘Roman’ studio pieces for David in 1796, and adding that they ‘had been made six or seven years before’ might also support 1791 as the birth date of the frame.

David (1748-1825), Self-portrait, 1794, o/c, 81 x 64 cm., and details of palmette-&-lotus bud frieze, Musée du Louvre

One of the principal markers of decorative style moving on from the NeoClassicism of Louis XVI to the overlapping, barely separable stages of Directoire, Consulat and Empire, is the way in which the ornaments employed by David were produced. Composition, plaster and papier mâché had been used to cast ornaments on modern movable frames since at least the first quarter of the 18th century in France; indeed, there had been quite an upset over this practice when, in 1722, it was brought before the guild of painters and carvers by an aggrieved client, forcing such frames to be stamped with (as it were) a note of their particular renegade ingredient [15]. The guild later withdrew its sanction from moulded ornament on frames, and its use only seems to have become more common again during Louis XVI’s reign. It was employed at first to replace the ornaments which were smallest and most repetitive – although these might also be used to train apprentice carvers, so, depending on workshop circumstances, runs of beading, pearls or rais-de coeur might be reproduced in plaster or remain as carved wood.

David (1748-1825), M. Pierre Sériziat, Salon de 1795, o/ panel, 129 x 95.5 cm., Musée du Louvre

With the fall of the monarchy, the flight and decimation of the aristocracy, and the lack of wealthy purchasers for their products, framemakers were forced to take economic measures – one of the most salient being to exchange the labour involved in carving each individual ornament on a frame for the labour of carving a single wooden mould, which could be used ad infinitum to cast the same motif over and over again. This was very bad for carvers, except where they could find work carving the moulds, or where artists demanded some individual variation from this embryonic trickle of mass-production.

The craft in France doesn’t seem to have switched with quite such wholesale abandon from carving to moulding as happened in Britain, but the use of cast ornament certainly diffused very widely from the 1790s onwards, and during the period of the Empire it spread throughout Europe. As well as economy of manufacture, it would bring in its way a sort of standardization of style, meaning that for the first time it becomes far more difficult to tell from the front of a frame whether it is an example of Imperial art from Italy, France, Germany or Spain.

David (1748-1825), (top left) Madame de Pastoret & her son, 1791-92; (bottom right) M. Pierre Sériziat, 1795; details of frames

Looking at details of David’s frames, it can be seen that he embraced the opportunities offered by a much greater use of applied cast ornament. Madame de Pastoret’s frame and Pierre Sériziat’s (and the pendant for his wife’s portrait) may well have been made in the same workshop with the same moulds, but the resulting ornament has been cut and placed in the hollow of each frame differently, to different effect.

On Mme Pastoret’s, the palmettes are spaced out; the lotus buds are higher up the curve of the profile and they spring less neatly from the volutes at the base of the hollow; on the Sériziats’ frames the palmettes and lotus buds are so close that they touch at the top, and the buds are set in little collars of leaves. The anthemia at the corners have also been compressed or lengthened, to fit the different space in the two frames; both of them are closely related to the bands of pierced anthemia on Georges Jacob’s chairs. The first (Pastoret) frame is more rhythmic, with light reflected from the reposes between the ornaments; the second is dense and rich, with a rather more sculptural effect.

The Sériziat portraits remained in the family [16] until about 1868, and then passed from the collection of Sosthène Moreau to the Louvre, ensuring that these are almost certainly the original frames.

David (1748-1825), Madame Récamier, 1800, o/c, 174 x 244 cm., and detail, Musée du Louvre

The portrait of Madame Récamier on her Jacob chaise longue remained with David until his death, and was bought from his posthumous sale through an intermediary by Charles X, so it is again almost certainly in the artist’s frame. This one alternates anthemia, springing from a ruffle of leaves and florets, with opening acanthus leaf buds; it also has egg-&-dart instead of pearls, perhaps to heighten the antiquity of the setting and props. The latter are almost completely undecorated, leaving the emphasis on the luminous figure of the sitter and the light-catching border of the frame – at once rich, light, dancing, and restrained between parallel lines. The ornament seems also to be relaxing and opening out; the Consulate moving towards the full splendour of the Empire style.

Percier & Fontaine

Charles Percier (1764-1838), Fragments of Classical architecture, before 1798, watercolour, pen-&-ink, 21 x 18.4 cm., Dr Moeller & Cie

Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine were born in the 1760s, and met as architectural students in the 1780s, either at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris or at its sister institution in Rome. Fontaine had won second place in the 1785 Prix de Rome, and although he wasn’t given a monetary scholarship he had the patronage of the baron de Bretuil, which enabled him to join the Académie in Rome [17]. Percier was given first place, with the accompanying scholarship, in the 1786 Prix de Rome; and both students stayed in Italy until the turmoil of the Revolution forced them, for various reasons, back to France.

Pierre Fontaine (1762-1853), L’Arc de Constantin et la Via Sacra à Rome, black chalk, pen-&-ink & watercolour, 22.7 x 40.3 cm., Christie’s Paris, 10 April 2008, Lot 142

They had spent their time rather as David had, studying and drawing the classical ruins in and around Rome, and bringing back a large number of images which would – again like David – provide them with references for their work.

Charles Percier (1764-1838), & Jean-Thomas Thibault (1757-1826), Sémiramis: an opera in three acts, design for set in Act 2, 1801, watercolour, gouache & black chalk, 33.5 x 37 cm., for Théâtre de l’Opéra-Montansier, May 1802, BnF Gallica

In 1792 they were employed together at the Opéra, designing and painting the sets, often with classical buildings and landscapes. These were ephemera, and few have survived; the design above is a slightly later example, made in 1801 by Percier with Jean-Thomas Thibault, giving an idea of the grandly monumental nature of the sets – which also helped to diffuse the decorative vocabulary of the Directoire and Empire styles.

In or around 1794, Percier and Fontaine were introduced to the marquis de Chauvelin, deputy French ambassador to London and a supporter of the Revolution, who commissioned them to refurbish his house in the rue de Chantereine [18]. François-Joseph Bélanger, who was responsible for the Directoire style inside the Hôtel de Bourienne, had built another house in this genre for the dancer and courtesan Anne-Victoire Dervieux (later his wife), also on the rue de Chantereine, in 1788; and in 1795 Joséphine de Beauharnais moved into the same road.

Jean-Baptiste Isabey (1767-1855), Joséphine de Beauharnais, shield-shaped miniature, 7 x 3.1 cm., in blue enamel frame 8.1 x 4.2 cm., Osenat, Fontainebleau, 29-31 May 2020, Lot 3; David (1748-1825), study of a shield from Album of drawings 11, folio 22, recto, Department of Prints & Drawings, Musée du Louvre; RF 54377

She visited Chauvelin’s house, and wanted to commission Percier and Fontaine to work for her – they were apparently introduced to her, not by the marquis, but by David’s ex-student Jean-Baptiste Isabey, who was painting Joséphine’s portrait at the time. The rue de Chantereine must have been a positive nucleus of the evolving NeoClassical style in painting, architecture and interior decoration, as it moved through the influence of the Directorate towards the settled star of the Empire; it is only a shame that none of these houses has survived.

A-P. Martial (1827-83), ‘Rue de la Victoire Hôtel Bonaparte d’aprés un croquis de 1798’, Ancien Paris: 300 feuilles, Bibliothèque national, and a reconstruction of the pavilion and house for an exhibition at Malmaison in 2013-14

Napoleon met Joséphine in the house on the rue de Chantereine (later the rue de la Victoire) in the autumn of 1795; six months later they were married, and Percier and Fontaine continued to refurbish the house as both the location of society salons and the pied-à-terre of a soldier and statesman. The military pavilion attached to the side of the house, however, was apparently Joséphine’s idea before she encountered Napoleon, and it marries a romantic idea of mediaeval jousts with Roman military trophies and contemporary army encampments. It illustrates the ability of both Percier and Fontaine to borrow, blend and transform their sources, and to remake historical and antique styles for a modern age.

Napoleon himself was away for much of the following two years, only living with Joséphine from December 1797 to the beginning of May 1798, and it was during this interval that he was introduced to David for the first time, the latter having written to him, expressing his admiration and asking for details of the Battle of Lodi the previous May so that he could paint it accurately. They met in December 1797, and David executed his first portrait of Napoleon, who in early 1800 offered him the post of official artist to the Consulate [19]. One of his students later explained why David refused such an honour:

‘This offer was negligible in view of the fact that he wished to be made, not painter to the government, but Minister of Arts, and the first painter in France… He wanted to conquer and rule the Republic of Arts’ [20].

David, in effect, seems to have operated far more like a Renaissance artist than his peers, in that – beyond the large number of paintings and drawings he produced and the students he taught – he would organize and design events for the Consulate and Empire, he invented Republican costumes for citizens, the State and all branches of the law [21], he played a major part in establishing the extensive vocabulary of Imperial symbols and motifs, and he designed and decorated furniture – and of course frames. His ambition to be more than merely the State artist, but to run the fine and applied arts of all France (and later, perhaps, of Europe) takes his versatility to its logical end.

Malmaison

David’s self-introduction to Napoleon was to bring him, Percier and Fontaine, and the archaeologist Vivant Denon [22] together in collaboration as the four main pillars of the Napoleonic style; but Percier and Fontaine must have been intensely aware of the impression which David had already made on the decorative arts, through the designs which Georges Jacob had realized for him from the mid-1780s, and through ‘the Etruscan ornaments [which David’s students] painted on their frames’ [23] and which Isabey may have reported or shown to them.

Salle du Conseil, Château de Malmaison. Photo: Pierre Poschadel

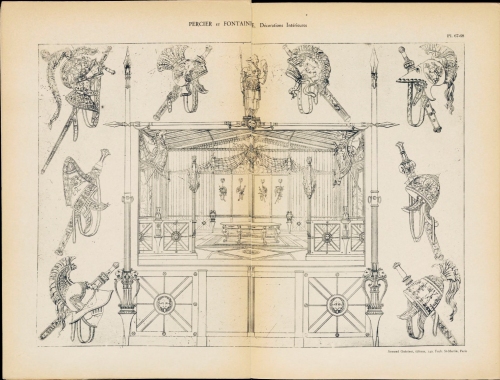

Percier et Fontaine, Recueil de décorations intérieures, Pl. 67-68, 1812, design for the Salle du Conseil and military trophies, Château de Malmaison. Internet Archive

In 1799, the year that Napoleon took charge of the French government, Joséphine acquired the château de Malmaison, which became an outpost of the French Consulate until 1802. Here Percier and Fontaine remade the whole house in the new, post-revolutionary, post-monarchical language of the Directoire (since styles are not amenable to exact dates and rules), with even more tents and military trophies.

(left) David, sketches of swords from Album of drawings 1, folio 41, verso, Department of Prints & Drawings, Musée du Louvre, RF 4506, 66; (centre) David, sword & scabbard designed for the Ecole de Mars, 1794, steel, bronze, wood, brass, scarlet fabric, Osenat, Fontainebleau, 4 December 2022, Lot 26; (top right) detail of armchair by Georges Jacob after a model by David, c.1786-89; (bottom right) Percier & Fontaine, detail of military trophy, Recueil de décorations intérieures, Pl. 67-68

Details of related items and designs by those involved already show the agreement of forms and motifs amongst them, some of which had been established and used by David from the mid-1780s-90s.

Jacob Frères (fl.1796-1803), armchair, c.1800, beechwood, bronze, parcel gilt and painted, wool upholstery, 96.5 x 67.9 x 71.1 cm., one of a suite of chairs designed for the Salle du Conseil, Malmaison, New York Historical Society

Georges Jacob appeared again, to supply furniture to Malmaison (he was now running his workshop as Jacob Frères with his son). He produced a softened, curvaceous and more comfortable version of a Roman-style Consular chair, in which David’s earlier design for his studio looks as though it has mated with a Louis XV bergère. However, the motifs which decorate it, gold on dark wood, are from the same vocabulary of ornament which David had been assembling from his Prix de Rome days, and which conveyed the sober authority and moral sense of honour he had seen in the Roman Republic and wished might be expressed in the new government of France.

Percier et Fontaine, Recueil de décorations intérieures, Pl. 2, 1812, Metropolitan Museum, design for a painter’s studio (!), Metropolitan Museum, New York

In their drawings, later engraved, Percier and Fontaine left the decorative arrangement of the frame to David. They created, borrowed and pulled together all sorts of Roman ornaments and symbols for friezes, ceilings, pilaster panels and trophies in the pursuit of an integrated interior, but in designs like this (above) for the elevation of a wall, the frames for painted or modelled scenes and figures are simplified to linear borders; or, in the centre overmantel-like frame, to a vestigial garland of bay leaves punctuated with rosettes.

Auguste Garneray (1785-1824), Vue de Salon de musique de Joséphine, c.1812, watercolour, 66.5 x 91 cm., Château de Malmaison

However, in the actual rooms of Malmaison as they appear in contemporary pictures, the rather sterile panels of the Recueil… leap into colourful life with a generous hang of paintings in gilded frames from sofa back to ceiling; and it is clear that many of the frames are in David’s pattern – a concave moulding full of palmettes or anthemia and a flat frieze. Just as the walls of Baroque Italian palazzi were covered in ‘Salvator Rosa’ frames, or the Palatine galleries of the Palazzo Pitti with Mannerist ‘Medici’ frames, so the walls of post-Revolutionary France were steadily filling with Directorate/ Empire frames.

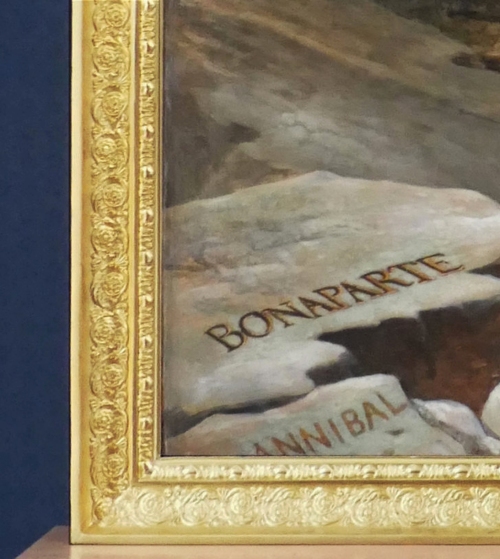

David (1748-1825), Napoleon crossing the Alps, 1800-01, o/c, 261 x 221 cm., and detail, Château de Malmaison

One of David’s last notable works before his consular patron became his emperor was the first version of Napoleon crossing the Alps, now hanging in Malmaison, but commissioned for Carlos IV of Spain. It later fell into the possession of Napoleon’s brother Joseph when, following Carlos’s abdication in 1808, he was installed as King of Spain; and when in his turn Joseph was forced to flee before the Portuguese and British armies, he took the portrait into France, and then to America. It was given to Malmaison by Joseph’s descendants in 1949, and its very chequered history makes it difficult to know the status of the frame.

The painting might well have been framed in Paris before being sent to Spain, since it had cost Carlos 24,000 francs, and the frame would both have finished and protected it; however, it is eight-and-a-half feet high, making canvas plus frame both heavy and difficult to manoeuvre. It was also intended to fit in with a series of similar portraits in the royal palace in Madrid, which might have had their own livery frames. Then again, would Joseph have taken the frame as well as the portrait out of Spain when he fled to France? – and if so, would he then have taken it across the Atlantic? The question is further complicated by the exasperating French museums’ habit of regilding slightly time-worn frames to the brilliantly shiny and imperfectionless finish beloved by German galleries and Italian dealers. The frame has been toned down in the image above in order to have some slight coherence with the painting it holds, but its native complexion is like platinum ormolu. Percier and Fontaine might have passed it, but not David; this is almost certainly a cuckoo frame in the Malmaison nest. Needless to say, it is nothing like the frame on the version of the painting in Charlottenburg, nor like the one in Vienna.

David and the Emperor

David (1748-1825), Coronation of Napoleon I and his empress Joséphine in Notre-Dame, 1806-07, o/c, 621 x 979 cm., and detail, Musée du Louvre

In 1804 Napoleon had himself elected Emperor, in order to stabilize his rule and avoid repeating the excesses of the Revolution, and on 18th December that year David was named premier peintre de l’empereur. His first commission was to paint the coronation (elements of which he had arranged himself), a task which took him two years, after which this vast and panoramic group portrait entered the State collection (1808). It has a very plain frame, with an elongated egg-&-dart moulding, slightly raked from the centres outwards, and – since the canvas is wider than the length of a London bus – what is probably the world’s longest run of rais-de-coeur at the sight edge. The lack of other ornament is probably due to the vast size of the canvas, which has little need to detach itself from the wall it hangs on, or requirement for aids with the recession of the internal space, or emblems declaring it to be imperial.

Louis Léopold Boilly (1761-1845), The public viewing David’s ‘Coronation’ at the Louvre, 1810, o/c, 61.6 x 82.6 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Léopold Boilly’s record of David’s painting is particularly accurate, as he asked the artist for permission to copy the Coronation and was invited in a very friendly and welcoming manner to visit David’s studio, and also his lodgings. He shows it during one of its public exhibitions hanging in what seems to be an even plainer frame than in the current example, but which may just be a reporter’s simplification, and is perhaps an institutional solution to presenting such an abnormally large painting.

Veronese (1528-88), Marriage at Cana, 1562-63, o/c, 677 x 994 cm., Musée du Louvre

Veronese’s stolen Marriage at Cana, for instance – another vast painting (fractionally bigger even than the Coronation) full of life-size or slightly larger figures – has four great golden beams containing it, where the only relief from plainness is the interplay between concave, convex and flat mouldings. Napoleon’s France was spending a lot on war and was also losing agricultural workers, etc., to conscription, affecting food production; its international trade was severely circumscribed by blockades enforced on its seaports, whilst taxes rose and the market for luxury goods shrank markedly.

Whilst Percier and Fontaine were maintaining the panoply of state (if in moulded plaster rather than carved giltwood), there were further economies to be made wherever possible in the arts, and these very simple, undecorated frames may be a symptom of the opposed wishes to compete with the memory of the ancien régime whilst doing it as cheaply as possible (see also Napoleon’s non-bejewelled ‘Charlemagne crown’). The Louvre’s plain livery frames (like those noted above on David’s The oath of the Horatii and The lictors bringing his sons to Brutus) may also be the result of this tension.

David (1748-1825), Pope Pius VII, 1805, o/panel, 88 x 72 cm., Musée du Louvre (commissioned by Napoleon I)

On the other hand, the portrait of the man who conducted – or should have conducted – the coronation is housed in a wide and richly decorated Empire frame, with an ornamented frieze and an extra tier of moulding, restoring to him the dignity which was taken away when Napoleon removed the crown from his hands and crowned himself. The Coronation is more than 90 times larger than the painting of Pope Pius – who also appears in the ceremony, at the moment he is forced to watch Napoleon raise in his own hands the crown he has taken from the pope – and it is packed with colour and portraits and muted reaction; whilst the image of the pope by himself is a spare and static pyramid of velvety red, capped by an ascetic face against a shaded grey ground. His stole is embroidered with delicate gold and silver sprays of leaves and bows, and his chair has a frame-like golden border of carved palmettes and buds, but it is the actual picture frame in this case which has the most intricate and extensive decoration.

David, Pope Pius VII, detail

Anthemia spring from scrolling leaves tipped with berries, and alternate with unfurling acanthus leaf buds; the astragal beneath the ogee forms long shaped beads and little discs; the frieze has a continuous running ornament of oak leaves and acorns, sunflowers and quatrefoils, characteristic of the Empire style; then there is a ribbon-&-stave moulding, and rais-de-coeur at the sight edge. The very low relief plaster ornament creates a subtle shimmer of light and movement around the portrait, contrasting with its intense stillness. It is a great portrait, conveying the sense of a man aware of his responsibilities to the Catholic world in the dangerous shadow of the man he came to Paris to crown, and the frame (which David must have organized himself) is an instrument of this revelation and an intimation of the power of the pope himself.

It should just be noted that the second version of the Coronation (1808-22), which hangs in Versailles along with David’s second massive commission from Napoleon, The distribution of the eagles (finished 1810), was intended for the throne room of the Tuileries – both of them were – and they would probably have been quite plainly framed amid the opulence of carpets, thrones, upholstery and the colour and celebration of the paintings themselves, just like the first version of the Coronation.

The Coronation Room, Château de Versailles, with David’s Coronation on the left and his Distribution of the eagles on the right; detail of the frame on the Versailles Coronation

However, in 1833, during the reign of Louis-Philippe, who, like his father, Philippe, duc d’Orléans, had been brought up as a liberal and had at first sympathized with the Revolution, the Coronation Room at Versailles was redecorated in a kind of homage to Napoleon, and both paintings were installed there in a gilded splendour of carved wood and general golden wedding cakery. The interior was designed by Pierre Fontaine and Frédéric Nepveu, the stuccos and carving executed by Jean-Baptiste Plantar (with joiners and possibly other woodcarvers), and the gilding by the artist Jean-Baptiste Joseph Jorand [24].

After Napoleon, mythology

Napoleon returned from exile on Elba to Paris in March 1815, and visited David in his studio in April, making him a commander of the Légion d’honneur. However, the Battle of Waterloo took place in June of the same year, and by October Napoleon was again in exile – this time on St Helena. By January 1816 David had been also been banished from France, along with all those who had voted for the death of Louis XVI, and had moved with his wife to Brussels [25]. He was wooed on behalf of the king of Prussia to settle with his wife in Berlin, at the same time that the Duke of Wellington was threatening all French passport-holders in Brussels with expulsion.

David (1748-1825), Comte Henri-Amedée-Mercure de Turenne-d’Aynac, 1816, o/c, 71.8 x 56.2 cm., Clark Art Institute

He still had a clientele amongst his fellow exiles; one of these was the Comte de Turenne, in whose family this portrait descended until 1999, supporting the authenticity of the frame. The design in the upper concave moulding, with palmettes and leaf buds, is the same as the pattern used for the portraits of David’s brother- and sister-in-law, the Seriziats, whom he had painted twenty-one years before; but the frame itself has the greater width of an Empire pattern, with the pearl moulding moved down a step below the second hollow, and the rais-de-coeur at the sight edge pushed out beyond the added frieze.

How was this made? – did David go to Brussels with some reverse boxwood moulds packed in his luggage? – or was his design by now so widespread that it could be found in any European city? Perhaps he took some frames with him into exile, and had new moulds made from those… or perhaps Turenne simply took the painting back to France with him in the 1820s and sought out David’s framemakers, or his students.

David needed money to live on in Belgium, and he continued to paint portraits. However, this was an undertow to his other activity, which was the realization of mythological scenes in settings and with hair and costumes of archaeological accuracy; mythological scenes which appear sometimes to be linked with the loss of his hero, Napoleon, to imprisoment on St Helena.

David (1748-1825), Cupid and Psyche, 1817, 184.2 x 241.6 cm., Cleveland Museum of Art

This painting has another very ornamental Empire frame, with four orders of decoration: a rope moulding at the back edge; anthemia and lotus buds in the hollow; an astragal-&-bead, where the astragals are shaped as elongated leaf buds; and an ogee with cross-cut bay leaves, also elongated, at the sight edge. This is another painting on a grand scale – eight feet across and six feet high, with life-sized figures – and the width of the frame rails, along with the accreted ornament, helps to give presence and weight to the picture within the gallery where it hangs. The painted bed is a more solid version of the Georges Jacob day-bed in Paris and Hélène, painted 29 years earlier, and it shows the influence of the imperial vocabulary assembled by Percier and Fontaine and the artists working for Napoleon. It includes stars and branches of bay leaves, both of which can be found on frames made in the Empire style, and often associated with bees (chosen by the Conseil d’État in 1804, along with the eagle, as Napoleon’s heraldic animal [26]).

Théodore Géricault (1791-1824), Mounted trumpeters of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, 1813-14, o/c, 23 3/4 x 19 1/2 ins (60.4 x 49.6 cm., National Gallery, Washington DC

Butterflies – one is also on the base of Psyche’s bed – were used in the wider vocabulary used for court decoration, as standing for the soul, and being associated with love and immortality; the butterfly hovering above Psyche (whose name means ‘butterfly’ and ‘soul’) is very close to the gilt bronze butterflies made by Francois-Jacob-Desmalter to decorate a secrétaire.

Géricault, Mounted trumpeters, detail

Perhaps David may initially have thought of using a frame with butterflies replacing the anthemia, as on the frame which has so strangely found its way onto Géricault’s mounted soldiers, but it may have been too difficult to organize in his place of exile.

David (1748-1825), The farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, 1818, o/c, 88.3 x 103.2 cm., J. Paul Getty Museum

Telemachus and Eucharis, however, has a quite different run of ornament in the hollow, which is now the lone large field on a frame delimited by pearls at the sight edge, and egg-&-dart on the back edge (look how beautifully this moulding has been measured to ensure that the eggs at the corners will join together in heart shapes). The subject of the painting is one of David’s moral nudges from antiquity – Telemachus, although very much in love with Eucharis, is dutifully preparing to leave her in order to search for Odysseus, his father, who left Troy after its fall along with the rest of the Greek army, but will eventually take ten years to get home to Ithaca. This is evidently a sort of vague analogy to Napoleon, who has followed his duty in fighting on for the French Empire, although he has been captured by the Allies and is now imprisoned on the island of St Helena, just as Odysseus was imprisoned on Calypso’s island for seven years.

David, The farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, detail

The expression here of Republican morality and responsibility (paralleling that in The oath of the Horatii and The lictors returning his sons to Brutus) is underlined by the ornament in the hollow of the frame, composed of anthemia alternating with garlands of bay leaves, the reward of the victor for courage in battle. The anthemia, or honeysuckle flowers, are particularly soft and flowing, and symbolize the feminine grace and selflessness of Eucharis, in opposition to the courageous resolve and steadfastness of Telemachus.

David (1748-1825), The wrath of Achilles, 1819, o/c, 105.3 x 145 cm., Kimbell Museum

The wrath of Achilles has a similarly important decorative and symbolic frame, carrying a related political emphasis. The profile has returned to the double scotia of other Empire frames, and the ornament includes piastres enriched with starflowers on the top edge and rais-de-coeur at the sight edge, whilst the larger scotia or hollow is decorated with alternating palmettes springing from a mask of Zeus, and sprigs of oak leaves and acorns, with anthemion corners.

The frame is intimately bound up with the painted scene, which is taken from an incident at the beginning of the Trojan War and looks forward to other episodes during the war. Achilles, who was to have been married to the princess, Iphigenia, learns from her father Agamemnon that instead she is to be sacrificed to Artemis, so that the winds will rise and blow the Greek fleet to Troy. Iphigenia is – shockingly – attired in white for her own funeral, rather than in the yellow robe of marriage, which makes Achilles’s realization and reaction even sharper and more immediate.

Later in the conflict, Agamemnon will act again against Achilles, removing the captured Trojan girl (Briseis) who had been his prize, in order to return her to Troy along with Agamemnon’s own prize, Chryseis, and thus placate the animus of the god Apollo towards the Greeks. Zeus had tried to remain neutral in the war between Greeks and Trojans. However, Achilles’s mother, the nymph Thetis (whom Zeus had once desired) intervened after the quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles over Briseis; Achilles went and sulked in his tent, and Thetis went rushing off to Zeus – at which point Zeus agreed to take the side of the Trojans, punish the Greeks for their treatment of Achilles, and also to preserve Achilles from death.

David, The wrath of Achilles, details

The story of Achilles is expanded by the motifs on the frame, which indicate the future (so to speak) of the episode which David has painted. The oak leaves and acorns in the hollow are realistically moulded at the top of the sprig, but extended at the bottom for ornamental effect; however, they are still immediately identifiable as representing the oak. They are also symbolic, since the bearded masks in between represent the head of Zeus, the oak being his sacred tree. This is therefore a painting of the first wrath of Achilles, when Zeus was neutral in his rôle of father of Olympus, and simultaneously looks forward to the second, when he takes the Trojan side – which will precipitate all sorts of awfulness, and end with the death of Achilles’s lover Patroclus. This makes the psychological tensions of the painting even more poignant.

There is a link to Napoleon in these decorative and symbolic motifs, as there is in the frame of Telemachus…: when he was proclaimed emperor of France, he chose emblems which connected him to ancient dynasties (e.g. bees > the Merovingians), but also to powerful myths (the eagle > Zeus). David’s painting and its frame, by using the oak tree and mask of Zeus, create an analogy between Achilles, the badly-treated hero, and Napoleon, the heroic but betrayed leader. There are also echoes of Napoleon in the powerful captain commanding unquestioning duty from his men, as Agamemnon did; and in the conquering force which, by 1811, ruled much of Europe, just as Zeus ruled gods and men. Interestingly, the oak tree had been considered as an emblem for Napoleon, but was rejected in favour of the eagle.

David (1748-1825), Mars disarmed by Venus and the three Graces, 1822-24, o/c, 308 x 265 cm., Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

Mars disarmed by Venus and the three Graces is David’s last painting, and – like The wrath of Achilles – seems to be linked to Napoleon and his fall. The features of Mars, god of War, appear to be based on David’s early, unfinished sketch of Napoleon made in 1797-98, which remained in the artist’s possession and was bought from his posthumous sale by Vivant Denon in 1826.

Mars, from Mars disarmed…, detail; and General Bonaparte, 1797-98, o/c, 81 x 65 cm., image reversed, Musée du Louvre

If the sketch is reversed, the two faces are uncannily alike – nose, brow, Cupid’s bow mouth and cheekbones – but rendered superficially unlike by the colouring, beard and hairline. Perhaps, then, this is a secret image of Napoleon, who has returned triumphant from battle to be disarmed by the softer arts of life, rather than being defeated and marooned by the Allies on a small faraway island? This is his official painter’s remaking of his legend, presenting him as still heroic, still the god of War, and only to be disarmed by Love and the Graces, and is possibly why David announced this work so definitely as his last.

David (1748-1825), Mars disarmed, detail

The frame may also play a small part in this undercover Napoleonization of Olympus. Unlike others of David’s frames, it has a frieze decorated with regular floral paterae, which recall the interiors illustrated in Percier and Fontaine’s Recueil de décorations intérieures. Floral paterae are used in just the same way on the frieze of the entablature below a ceiling (plates 25 and 39), or around the central frame on a wall panel (plate 31).

Louis Lafitte (1770-1828), Pompeiian dancer, c. 1800, grisaille on stucco with polychrome border, Château de Malmaison

In real, visitable form, they are close to the framing borders of Louis Lafitte’s large grisaille panels of eight classical dancers, with other panels of tripods, etc., in the dining-room at Malmaison. David must have been very familiar with this room, created for Napoleon and Josephine together and furnished for them by Georges Jacob. Perhaps it symbolized for him the place to which Napoleon retreated like Mars after victory in battle, and where he was happiest.

Such small floral paterae may seem an insignificant detail to shore up this kind of theory, but looked at closely it can be seen that they are sunflowers – the flower of Apollo, god of the sun and the arts, and linked in other ages to those monarchs who patronized the creators of painting, architecture and the decorative arts: Charles I and Van Dyck in England, and Louis XIV and countless artists in 17th and early 18th century France. Mars disarmed… may represent many other things, but at least a thread amongst its meanings may be the old painter’s tribute to the leader who was his own Apollo, as well as his Mars.

David’s students

Some of the many pupils who flocked to the ‘vast, sombre space, formed in part by the great walls of the Louvre’ [27], went on to produce their own imaginative or innovative frame designs, or chose well from the fashions available to them, or replicated those introduced by David with particular élan.

These include:

Marie-Guillemine Benoist (1768-1826), Portrait of Madeleine, 1800, o/c, 81 x 65 cm., Musée du Louvre

Marie Guillelmine Benoist (1768-18260, Mme Philippe Panon Desbassayns de Richemont & her son Eugène, 1802, o/c, 116.8 x 89.5 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York. Photo with thanks to Keith Christiansen

Michel Martin Drolling (1786-1851), Alix de Tournon Simiane, c.1847, o/c, 774 x 59.5 cm., and detail, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Christoffer-Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783-1853), Frederik VI of Denmark, 1820, o/c, 46 x 37 cm., Sotheby’s, 19 January 2016, Lot 176

François Gérard, Baron Gérard (workshop; 1770-1837), Portrait of Napoleon in coronation robes, c.1805-14, o/c, 82.2 x 65.5 cm., frame attributed to Delporte Frères, and detail, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montreal. Photo of frame: Christine Guest

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (1767-1824), Mlle Lange as Danäe, 1799, o/c, 60.33 x 48.58 cm., and detail, Minneapolis Institute of Art

Antoine-Jean Gros, Baron Gros (1771-1835), Bacchus & Ariadne, c.1821, o/c, 90.8 x 105.7 cm., and detail, National Gallery of Canada

Louis Hersent (1777-1860), Cardinal Anne-Antoine-Jules de Clermont-Tonnerre, autograph replica of 1825 original, o/c, 72 x 50 cm., and detail, Artcurial: Cent portraits pour un siècle, 15 February 2022, Lot 100

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), Madame Leblanc, 1823, o/c, 119.4 x 92.7 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York. Photo with thanks to Keith Christiansen

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), M. Bertin, 1832, o/c, 116 x 95 cm., and detail, Musée du Louvre

Johan Ludwig Lund (1777-1867), Frederik VI in an admiral’s uniform, o/c, 126 x 108 cm., Art market

François-Joseph Navez (1787-1869), Portrait of David, 1817, o/c, 74.5 x 59.5 cm., Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels. Photo: Sailko

Jean-Baptiste Wicar (1762-1834), Virgil reading the Aeneid to Augustus, Octavia & Livia, 1790-93, o/c, 111.1 x 142.6 cm., Art Institute of Chicago. Photo: Sailko

****************************************************

[1] See Paul Mitchell, ‘A signed frame by Jean Chérin’

[2] Anton Mengs, Reflections on beauty and taste in painting, 1762

[3] Johann Winckelmann, Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums, or History of the art of antiquity, 1764

[4] Thomas Pelzel, ‘Anton Mengs and his British critics’, Studies in Romanticism, vol. 15, no 3, 1976, Summer, p. 409

[5] Nine hundred casts from Mengs’s collection were acquired after his death in 1779 by Frederick Augustus III, and five hundred still survive in the Semper Gallery in Dresden; see Rolf Johannsen, Vorbild Antike, 2020. Mengs had also donated another group in 1776 to the king of Spain, to be displayed in the Royal Academy there; see Janis Tomlinson, ‘A report from Anton Mengs on the Spanish Royal Collection’, Burlington Magazine, vol. 135, no 1079, February 1993, p.97

[6] Noémie Etienne, ‘A family business: picture restorers in the Louvre Quarter’, Journal18, no 6,

[7] See ‘Antoine Lavoisier’

[8] Sarah Medlam, ‘Callet’s Portrait of Louis XVI: A picture frame as diplomatic tool’, Furniture History: Journal of the Furniture History Society, XLIII, 2007, p. 146

[9] See Jean-Henri Cless, Un atelier d’artiste, présumé être celui de David, c.1804, Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris

[10] Etienne-Jean Delécluze, Louis David, so école et son temps, souvenirs, 1855, pp. 20-21 . See also Georges Wildenstein, David, 1963, p.29

[11] ‘Lampes à Quinquet’ were a version of Argand oil lamps, and were called after their inventor, Antoine-Arnoult Quinquet (1745-1803), who may have been responsible for adding a glass chimney to Argand’s initial design

[12] Delécluze, op. cit, p. 21

[13] Information with thanks to Jacob Simon

[14] See the entry on the museum’s website

[15] Bruno Pons, ‘18th century French frames and their ornamentation’

[16] This was also David’s wider family, as Mme Seriziat was his sister-in-law

[17] Paul Léon, ‘Les tribulations d’un architecte: Fontaine et Napoléon’, Revue des Deux Mondes (1829-1971), 15 June 1956, p. 578

[18] Ibid.

[19] Wildenstein, op.cit., p. 6

[20] Ibid.

[21] David’s costumes were engraved and added to by Vivant Denon (1747-1825): L’oeuvre originale de Vivant Denon, Sixième sèrie, ‘Oeuvres français de la Convention’, pub. 1873, BnF Gallica

[22] Vivant Denon did not approve of David, nor of the large sums Napoleon paid for his paintings; Wildenstein, op. cit., p. 6

[23] Delécluze, op. cit, p. 21

[24] Justine Gain, ‘Stuccos for Versailles: Jean-Baptiste Plantar’s decorative work for the Historical Galleries (1833-48)’, Grupo Español de Conservacion, Ge-conservation, no 23, 2023

[25] Wildenstein, op. cit., pp. 127-28

[26] See ‘Bees in the frame: Part 2 – the Napoleonic bee’

[27] Delécluze, op. cit, p. 17