Framing the European paintings at The Metropolitan Museum: Part 2

by Keith Christiansen

The 18th and 19th centuries in Italy, France and beyond

18th century Italy: Venice, Bologna and Rome

Venice

Parlour of the nuns of San Zaccaria, Ca’ Rezzonico, Venice. Photo: Didier Descouens

Parlour of the nuns of San Zaccaria, Ca’ Rezzonico, Venice. Photo: Didier Descouens

In 18th century Venice the potential rôle of the art dealer as the person who decided which frames would complement the pictures best and promote their sale comes clearly into focus in the person of Joseph Smith (c.1682-1770). A long-term resident in the city and from 1744 to 1760 British consul in Venice, he combined an acute business sense, a love of painting, and a network of contacts. By 1730 he had established a business relationship with Canaletto and become the primary conduit for the sale of the artist’s paintings to British collectors. After the works were delivered to him, Smith would see to the framing and packing.

Canaletto, four views of Venice: Campo Santa Maria Zobenigo; The Grand Canal, looking south-east; Campo Sant’Angelo; The Grand Canal, looking south towards the Rialto Bridge; all 1730s, o/c, 47 x 78.1 cm.; 47 x 77.8 cm.; 46.7 x 77.5 cm.; 46.4 x 77.5 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Canaletto’s series of four views of Venice in The Met’s collection date from the 1730s and are in the original frames chosen by Smith – identical to those he put on other pictures, including some now in the British Royal Collection and others belonging to the Duke of Bedford.

Canaletto (1697-1768), Piazza San Marco, late 1720s, o/c, 68.6 x 112.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

They are notably narrow, with an enriched floral chain of opposed ‘C’ scrolls which distinguishes them from the more typical Venetian Rococo frame, like that on Canaletto’s Piazza San Marco, which is of the period but not original to the picture.

Canaletto (1697-1768), Warwick Castle, 1748, o/c, 42.9 x 71.8 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Canaletto painted the view of Warwick Castle during the nine years he lived in London, and its original frame is English in manufacture and design, [asymmetric about the horizontal axis, and with a prominent pierced rocaille fronton].

Pietro Longhi (1701-85), The temptation, 1746, o/c, 61 x 49.5 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Another Venetian painter who preferred idiosyncratic frames is the enchanting genre artist Pietro Longhi. Four of his works in The Met [1] still have their original, quite delicately articulated Rococo frames. Longhi actually depicts this sort of frame in some of his paintings and they doubtless formed part of his marketing strategy. One assumes that he had a special business relationship with a particular framemaker.

Canaletto (1697-1768), Campo Sant’Angelo, Venice, 1730s, o/c, 46.7 x 77.5 cm., and details, Metropolitan Museum, New York

As to that, in his depiction of the Campo Sant’Angelo Canaletto shows the shops and displays of goods of several carpenters or cabinetmakers. Framed paintings are depicted hung outside, waiting for a buyer – two oval and four rectangular pictures are shown in matching frames – whilst, in an adjacent workshop, two oval frames are seen propped against a wall. Similar oval frames, based on historical mouldings, were made only a quarter of a century ago for Giambattista Tiepolo’s pair of allegorical figures shown against gold backgrounds [2]. Two further paintings from the series are in the Rijksmuseum. They probably served as overdoors.

Bologna

Gaetano Gandolfi (1734-1802), Head of a bishop, c.1770, o/c, 46.7 x 37.8 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Ubaldo Gandolfi (1728-81), Execution of St John the Baptist, c.1770, o/c, 61.9 x 43.2 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Regional styles varied greatly in 18th century Italy. Two fairly typical examples of the sort of frames popular for cabinet-sized pictures in Bologna can be seen on Gaetano Gandolfi’s Head of a bishop, and The execution of St John the Baptist painted by Gaetano’s older brother Ubaldo. The labbretto (little lips) decoration around the openings is characteristic of Bolognese frames. Although of the period, neither is original to the picture.

Gaetano Gandolfi (1734-1802), Sacrifice of Iphigenia, 1789,o/c, 68.3 x 45.7 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

By contrast, the frame on Gaetano Gandolfi’s Sacrifice of Iphigenia, with elegant shells and vines decorating the corners, is original and unique in its design. The picture is an oil sketch or modello for the fresco’d decoration of a ceiling in Palazzo Gnudi Scagliarini, Bologna.

Giacomo Rossi (1751-1817), stuccowork in Palazzo Gnudi Scaliarini, 1789. Photo: Museo civico del Risorgimento di Bologna I certosa

The elegant and inventive stucco work in the palace was carried out by Giacomo Rossi, and it may be Rossi who also designed the frame. Certainly, there is a similar delicacy and sharpness, as well as a correspondence in the choice of motifs. Perhaps the owner of the palace, Antonio Gnudi, apostolic treasurer for the papal state of Ferrara-Bologna, retained the modello and had it specially framed to harmonize with the decoration of his rooms.

The Roman frame

Sala dell’Apoteosi di Martino, Palazzo Colonna. Photo: Sailko

In 18th century Rome, two kinds of frames – or rather, variants of a basic model – were especially popular. These designs are named by association with work by the painters Salvator Rosa and Carlo Maratta (or Maratti), and this may account for their compatibility with paintings of notably diverse styles – something which is evident to visitors to the collections of the Doria Pamphilj and Colonna families in Rome, in which the paintings are given uniformity by their presentation in ‘Salvator Rosa’ frames. This type of frame is distinguished by a Baroque sculptural profile, combining a hollow and a counterbalancing projecting element (or, more technically, a deep scotia and three-quarter-round rail).

Corrado Giaquinto (1703-66), The penitent Magdalen, c.1750, o/c, 160 x 118.1 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

A fine example, original to the painting, adorns Corrado Giaquinto’s The penitent Magdalen. Interestingly, a label on its reverse enabled the cardinal who commissioned the picture to be identified; it was Mario Bolognetti, treasurer of the Apostolic Chamber in the Vatican. An inventory drawn up after Bolognetti’s death lists the picture hanging in his bedroom together with five other works also by Giaquinto. The lack of ornamentation of the frame may seem the perfect complement to the picture’s penitential subject, but in fact it is a standard model we find on a whole variety of 18th century paintings, regardless of subject. The Salvator Rosa frame, in its various iterations, proved incredibly versatile.

Pierre-Hubert Subleyras (1699-1749), The mass of St Basil, 1746, o/c, 137 x 79 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Two discreetly ornamented examples can be seen on the The mass of St Basil by the Roman-based French painter Pierre Subleyras, as well as on his portrait of Pope Benedict XIV (also 1746).

Pierre-Hubert Subleyras (1699-1749), The atelier, 1740s, o/c, 125 x 99 cm., Academie der bildenden Künst, Vienna

The frame on the The mass of Saint Basil is not only original to the painting but was depicted around it in the artist’s The atelier, now in the Academie, Vienna.

Giovanni Battiata Gaulli (1639-1709), Clement X, c.1670-71, o/c, 77.5 x 61.6 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

A fine example of the other type of frame – the ‘Carlo Maratta’ – contains Giovanni Battista Gaulli’s Portrait of Pope Clement X. Maratta and Salvator Rosa frames proved enormously popular in England; indeed, the one on Gaulli’s portrait of Clement X is of British, not Italian, manufacture, having previously held a painting formerly ascribed to John Opie which the department de-accessioned! Maratta frames and its variants were the preferred choice of both Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough [3], though this is not necessarily evident from their pictures in museum collections. British portraits were generally of a few, uniform sizes and this enabled frames to be easily changed to suit the taste of the day, which complicates our ability to say whether a period frame on a picture is necessarily the one put on it by the artist or its first owner. In Britain in the 18th century many paintings were framed through the artists themselves, in order to control the design of the setting, or to stamp the painter’s identity on the overall work of art.

Gainsborough (1727-88), Cottage children (or The wood-gatherers), 1787, o/c, 147.6 x 120.3 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Reynolds (1723-92), Self-portrait, c.1780, o/c, 145.4 x 121.8 cm., frame attributed to Thomas Vialls, Royal Academy

Fine, British-made Maratta frames contain Reynolds’s portrait of Mrs Lewis Thomas Watson and Gainsborough’s Cottage children (The wood-gatherers); and it seems likely that the frame for which Reynolds paid 10 guineas in 1782 for his dazzling portrait of Captain George K. H. Coussmaker was not the very fine Louis XIV-style frame it is displayed in now, but a ‘Carlo Marat/Frame’ (as the artist referred to them in his accounts), such as he chose for his 1780 Self-portrait for the Royal Academy.

Romney (1734-1802), Self-portrait, 1795, o/c, 76.2 x 63.5 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Paradoxically, George Romney’s Self-portrait is also in a Salvator Rosa frame, though he actually preferred frames with a NeoClassical profile [4].

Salvator Rosa (1615-73), The dream of Aeneas, 1660-65, o/c, 196.9 x 120.7 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Ironically, the frame on Salvator Rosa’s marvellously evocative Dream of Aeneas is also a British Maratta frame and was doubtless put on the painting after it was sold to a British collector (the picture hung at Northwick Park, Gloucestershire from 1832 until 1964). Salvator Rosa’s melancholic Self-portrait in the Museum is now in an antique Italian Salvator Rosa frame, but this represents a curatorial initiative of the 1990s.

According to Maratta’s biographer and friend, Giovan Pietro Bellori, the artist also

‘introduced new models of black frames in pear wood, which imitate ebony, with very elegant gold carvings and a good dark background and which today are used everywhere, lending much grace to a painting’.

Conzen, Düsseldorf, 2018 frame auction, Lot 76, ‘Salvator Rosa’ frame in stained and polished walnut, late 17th – early 18th century

Similarly versions of Salvator Rosa frames were embellished with an egg-&-dart or acanthus-&-shield moulding at the back edge, a ribbon-&-stave below the top edge, and an applied acanthus leaf or acanthus-&-shield ogee at the sight edge, all picked out in water-gilding.

Michiel Sweerts (1618-64), Clothing the naked, c.1661, o/c, 81.9 x 114.3 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Although it was painted in Amsterdam, Michiel Sweerts’s affecting Clothing the naked is in the same type of frame, without the ribbon-&-stave moulding. It was put on the painting after its acquisition in 1981.

Paulus Bor (c.1601-69), The disillusioned Medea, c.1640, 155.6 x 112.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The Salvator Rosa frame on Paulus Bor’s The disillusioned Medea, which has a provenance going back to the Chigi family in Rome, also incorporates some of these features, once again demonstrating the versatility of this style of frame.

The artistry of frames in 18th century France: the Rococo

There is no question but that in 18th century Paris the making of frames achieved a level of craftsmanship and design which set a new standard. As was the case with Herman Doomer’s practice in 17th century Amsterdam, so it was in France: furniture makers of the calibre of Jean François Oeben, cabinetmaker to Louis XV, also produced picture frames [5]. And alongside traditional royal and aristocratic patronage, there was the increasingly important figure of the amateur and the emergence of a public forum for discussing issues of taste in the exhibitions at the Salon, inaugurated in 1751.

A remarkable testimony of a dealer’s response to this expanding world of collecting is provided by the example of the painter/gilder Guillaume Bouclet, who had a shop on the Île de la Cité. In his study of 18th century French frames, Bruno Pons cites Bouclet’s 1713 advertisement declaring that he

‘…makes and sells all kinds of work in paint, gilding and carving, such as oval & rectangular picture frames, looking-glass frames, clock & console bases, stands of porcelain or ormolu; he makes tabernacles, other Church furnishings and clerical staffs, chandeliers, reliquaries, religious & history paintings, Court portraits, paintings of flowers, fruit & landscapes for overdoors. He buys, sells and restores old paintings, relines and renders them like new; presents all kinds of prints in clear glass, made up in in cedar wood frames; he also mounts prints & drawings on canvas; supplies fluted moldings (gilded or plain); and in general whatsoever comes under the heading of art, all completed meticulously and at a reasonable price; and he undertakes all kinds of interior painting and gilding’ [6].

Watteau (1684-1721), The French comedians, c.1720, o/c, 57.2 x 73 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Fragonard (1732-1806), The two sisters, c.1769-70, o/c, 71.8 x 55.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Overall, the 18th century French frames in The Met’s collection are of remarkable quality and repay close study; many have online catalogue entries as well as drawn cross-sections compiled by Timothy Newbery and Cynthia Moyer. A short list would have to include the superb Régence frame on Watteau’s The French Comedians and the no less fine frame on the Fragonard’s Two sisters, the style of which is transitional between Régence and Louis XV. The latter has been enlarged on its vertical sides to fit the picture and thus cannot be original to it. Indeed, to judge from the fleur-de-lis in the cartouches at the corners and centre bottom, it must have been created for a royal portrait.

Greuze (1725-1805), Charles-Claude de Flahaut, comte d’Angiviller, 1763, o/c, 64.1 x 54 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The elegant Rococo frame on Greuze’s 1763 portrait of the comte d’Angiviller is earlier than the painting, but echoes his embroidered and lacy costume. The corners and centres are decorated with asymmetrical flourishes, half rocaille and half curling leaves, held in opposed foliate C-scrolls, whilst spiralling garlands of florets wind around the S-scrolled top edge.

François-Hubert Drouais (1727-75), Marie Rinteau, called Mademoiselle de Verrières, 1761, o/c, 115.6 x 87.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Fragonard (1732-1806), A shaded avenue, 1775, o/panel, 29.2 x 24.1 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The beautiful frames on Drouais’s Marie Rinteau and Fragonard’s A shaded avenue are in the same vein. The extraordinary Fragonard frame (not original to the painting) is carved overall, leaving no surface free of decoration; its pendant has a matching frame, which is a 19th century copy.

Boucher (1703-70), Madonna & Child, St John the Baptist and angels, 1765, o/c, 41 x 34.6 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

A Rococo frame which is original to the painting contains Boucher’s Madonna & Child; the wonderfully intricate yet rigorously symmetrical decoration, with a shell held in rocailles at each corner, epitomizes the refinement of this style.

Greuze (1725-1805), Aegina visited by Jupiter, c.1767-69, o/c, 147 x 195.9cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The finely-carved frame on Greuze’s Aegina visited by Jupiter is also almost certainly original to the painting, and another notable example from the 1760s. It is made in the Transitional style, revealing the gradual metamorphosis of the Rococo into the NeoClassical style, and has the intensely sculptural presence characteristic of work by the eminent Parisian framemaker Jean Cherin (1733–1785) [7], expressed in its striking curvilinear silhouette and richly articulated corners and centres. In 1760, Chérin was admitted to the Académie de Saint-Luc as a menuisier-sculpteur (a carpenter-sculptor), rather than a menuisier (carpenter-carver) or menuisier-ébéniste (cabinetmaker), and this distinction seems evident when his frame is compared with the very elaborate one surrounding Boucher’s cabinet-size Madonna & Child, above.

18th century France: the NeoClassical

Jacques-Louis David (1743-94), Antoine Lavoisier and his wife Marie Anne Lavoisier, 1788, o/c, 259.7 x 194.6 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The Louis XVI frame on David’s magnificent portrait of the Lavoisiers is completely different from the two previous frames in its rectilinear sobriety, but equally rich in its ornamental details. Although not original to the picture, the frame is more or less contemporary and of a type and quality associated with François-Charles Buteux (1732–88), framemaker to Louis XVI [8]. The cartouche at the top is ornamented with the royal fleur-de-lys and the Order of the Holy Spirit and would probably have held the royal crown above; it is supported with palm leaves, whilst floral swags are fixed to trompe l’oeil nailheads at the corners. The cartouche on the bottom would have been inscribed with the name of the recipient of the royal portrait (for example, the Buteux frame at Waddesdon on Callet’s portrait of Louis XVI states that the painting was given by the king to his ambassador to the King of Great Britain) [9]. The Lavoisier heirs sold the picture through Wildenstein & Co. to John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1924, retaining its original frame for themselves.

Main Reading Room, The Rockefeller University, c.1970s, courtesy of the Rockefeller Archive Center

For half a century painting and frame hung in the library of Rockefeller University, until in 1977, the university sold it to Charles and Jayne Wrightsman, who donated it to The Met.

Joseph Siffred Duplessis (1725-1802), Benjamin Franklin, 1778, o/c, 72.4 x 58.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Buteux also may have made the exceptional oval frame on Duplessis’s iconic 1778 Portrait of Benjamin Franklin. Rather than a cartouche, elaborately carved attributes decorate a wonderfully simple yet elegant Louis XVI moulding. As described by Cynthia Moyer in her online catalogue entry,

‘The frame is surmounted by a carved garland of olive, symbolizing peace and wisdom, and of laurel, used for the victor’s crown. Above it a branch of oak, a symbol of power, and another of American boxwood form a wreath. Entwined within the foliage forming the crest is an undulating rattlesnake…, the topic of a letter Franklin submitted anonymously to the Pennsylvania Journal in 1775. […] The frame’s drop pendant is composed of a central cartouche or shield with the Latin inscription VIR, meaning hero. The shield secures a draped muskrat pelt with snarling teeth, protruding tongue, claws, and a distinctive rat-like tail. The muskrat head on the right balances a Phrygian cap on the left, a symbol of liberty. […] Beneath, the pelt entwines a club, suggesting Hercules—the embodiment of truth, heroism, and determination—to whom Franklin was sometimes compared’ [10].

The frame both extolls the sitter and offers a remarkable contrast to his plain, unaffected appearance which so impressed French aristocrats (Parisians were astonished and delighted to see the balding American appearing in public without a wig—the seeming embodiment of the democratic ideal).

Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), Comtesse de la Châtre, 1789, o/c, 114.3 x 87.6 cm, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Vigée Le Brun’s striking portrait of the comtesse de la Châtre has another extremely fine Louis XVI frame, similar to the royal frame by Buteux. It has a guilloche moulding at the top edge, a fluted hollow or scotia, pearls, and acanthus at the sight edge; it is further embellished at the top with a Roman fronton decorated with piastre ornament and a ribbon bow, from which swags of bunched bay leaves emerge, and are caught on trompe l’oeil nailheads. Unadorned examples of this style of frame became popular throughout Europe.

Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), Madame Grand, 1783, o/c, 92.1 x 72.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749-1803), Self-portrait with two pupils, Marie-Gabrielle Capet & Marie-Marguerite Carraux de Rosemond, 1785, o/c, 210.8 x 151.1 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Pietro-Antonio Martini (1738-97),View of the Salon of 1785, 1785, etching, 27.6 x 48.6 cm., detail with Labille-Guiard, Self-portrait with two pupils, Metropolitan Museum, New York

There are further spectacular Louis XVI frames on Vigée Le Brun’s Madame Grand, which may be original to the portrait, and on Adélaïde Labille-Guiard’s Self-portrait with two pupils, [which is a later addition but presents it with great élan. The portrait is shown in the print above in a rectilinear frame for its appearance at the 1785 Salon; the current frame may have been applied when the painting passed through Wildenstein’s in the 20th century, and seems to have been given a new sight edge to fit it to the canvas ].

Marie-Denise Villers (1774-1821), Marie-Joséphine-Charlotte du Val d’Ognes, 1801, o/c, 161.3 x 128.6 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Antoine-Maxime Monsaldy (1768-1816) & G. Devisme (fl.c.1800-06), Vue des ouvrages de peinture, 1801, etching, 24.8 x 38 cm., detail with Marie-Denise Villers’s portrait, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Marie Denise Villers’s portrait of Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes, [has similarly been reframed since it was exhibited at the Salon in 1801, when, like the Labille-Guiard, it was displayed in a rectilinear frame. The NeoClassical fronton frame it has now may perhaps also have been found for it by Wildenstein; it is early for the date of the painting, but gives it considerable presence, bracketing the artist with Louis Vigée Le Brun and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard].

François-Hubert Drouais (1727-75), Boy with black spaniel, c.1767, o/c, 64.5 x 53.3 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

As expressions of refined taste, these frames enjoyed a revival in the 19th century, so it should be no surprise that the beautifully detailed Louis XVI-style frame on Drouais’s Boy with a black spaniel actually dates from c.1890, possibly having been modelled on an 18th century example by the sculptor/ framemaker Etienne-Louis Infroit (1720–94). [The flowers tangled in the carved ribbon fronton include roses, lilac, narcissus and daisies, probably with a general allusion to youth and beauty rather than any classical significance].

19th century France: Empire and Restauration

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), The death of Socrates, 1787, o/c, 129.5 x 196.2 cm., Metropolitan Musem, New York

For a lesson in sobriety there is the restrained articulation of the 19th century Empire frame on David’s masterpiece, the Death of Socrates. Its deep fluted hollow or scotia, and elegant detailing, with the corners ornamented with acanthus leaves and a ribbon-&-stave decoration beneath the scotia, serves as a foil for David’s concern for the archaeological authenticity of the setting of his moral drama.

Pietro Antonio Martini (1738-97) after Johann Heinrich Ramberg, Exposition au Salon du Louvre en 1787, etching & engraving, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The frame seems to be of British manufacture, c.1810, and thus is not the frame which was on the picture when it was exhibited in the Salon of 1787: the picture can be seen at the centre of the bottom tier of the print illustrated here.

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), General Étienne Maurice Gérard, 1816, o/c, 197.2 x 136.2 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon (1758-1823), Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord, Prince de Bénévent, 1817, o/c, 215.9 x 141.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

François, Baron Gérard (1770-1837), Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord, Prince de Bénévent, 1808, o/c, 213 x 147 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The Empire frames on David’s 1816 Portrait of General Étienne-Maurice Gérard and Prud’hon’s 1817 Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand have rigorously archaeological structures and details, incorporating classical anthemia; [David’s painting, executed when he was in exile in Belgium, has the same frame design as those he produced when in France as premier peintre de l’empereur [11], and Prud’hon’s follows the same fashion. However, the 1808 portrait of Talleyrand by Baron Gérard (although earlier than Prud’hon’s) has a later Restauration frame with scrollwork ‘Greek corners’, probably made between the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 and Talleyrand’s death in 1838].

Marie-Guillelmine Benoist (1768-1826), Jeanne Eglé Mourgue (Mme Desbassayns de Richemont) & her son Eugène, 1802, o/c, 116.8 x 89.5 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Marie-Guillelmine Benoist’s portrait of Madame Desbassayns de Richemont has an exceptionally extravagant and fully carved entablature frame [which is linked to those of her teacher, J-L David, by the frieze of anthemia and acanthus buds, but is otherwise much more sculptural than David’s frames [12], many of which, during and after the Revolution, relied almost completely on the use of moulded plaster ornament.

It has a top edge with a vertebrate moulding carved in the round and pierced, with (centred) delicate acanthus and bay leaf-&-berry along a stave; and an extraordinary ovolo on the convex moulding below this, where the ‘eggs’ are formed into pinecones held in acanthus leaves (they may also be loose representations of bunches of coffee beans, the source of the family’s wealth from their estates on Réunion). The astragal beneath this, on the outer edge of the frieze, is carved into round, flattened and spiral beads, and there are rais-de coeur at the sight edge. As the portrait remained in the family for the next century, and the frame appears to be unaltered, it is more likely to be the original.]

Tradition and innovation in 19th century France and elsewhere

Given the exalted place which frames and framemakers came to hold in 18th century Paris, it is fascinating to learn that Ingres sometimes gave not only general instructions about patterns and finish for the frames for his pictures, but occasionally designed their decorative details [13]. In the case of his painting of Stratonice and Antiochus for duc Ferdinand d’Orléans (Château de Chantilly), he was particularly concerned that the motifs on the frame should relate to the painting, and recommended consulting the architect Victor Baltard, who had assisted him in designing the architecture in the picture. Indeed, so important did Ingres consider the framing that he offered to assume the costs. For his Odelisque with a slave (Harvard Art Museums), he recommended a frame as ‘Baroque as possible’ to harmonize with its exotic Turkish theme.

J-A-D. Ingres (1780-1867), M. Bertin, 1832, o/c, 116 x 95 cm., and detail, Musée du Louvre

The range of his ideas is remarkable and expresses the exact opposite of the standardized Salvator Rosa and Maratta frames. For the 1832 portrait of his friend, the art collector and writer M. Bertin, he designed a frame embellished with grapevines, lizards and birds [14].

J-A-D. Ingres (1780-1867), Jeanne d’Arc au sacré de Charles VII, 1851-55, o/c, 240 x 178 cm., Musée du Louvre

Grapevines also enrich the original frame on his painting of Jeanne d’Arc au sacré de Charles VII, commissioned in 1851 by the state’s Director of Fine Arts (both works are in the Louvre) [15]. It is therefore particularly unfortunate that so many of the frames on Ingres’s paintings have been changed. The Met’s marvellous portrait of Joseph-Antoine Moltedo – the Corsican-born director of the post office in Napoleonic Rome – was painted around 1810, during the artist’s eighteen-year residence in Italy, but its restrained frame is in a Restauration design put on the painting at a later date.

J-A-D. Ingres (1780-1867), Madame Leblanc, 1823, o/c, 119.4 x 92.7 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The frames on the marvellous paired portraits of Jacques-Louis Leblanc and his wife Françoise Poncelle tell another story. The portraits were painted in Florence in 1823 – a year before Ingres’s return to Paris – and the frames are original to the pictures. However, it has been noted that the highly stylized lotus leaf-and-blossom pattern, as well as the more conventional detailing, point to France rather than Italy as the place of manufacture; and, if this is so, the frames may well have been put on the pictures following the Leblancs’ return to Paris and prior the portrait of Mme Leblanc being lent to the 1834 Salon. Given Ingres’s friendship with the Leblancs, it is possible he advised the sitters on framing their portraits.

J-A-D. Ingres (1780-1867), Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn, Princesse de Broglie, 1851-53, o/c, 121.3 x 90.8 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

His magnificent portrait of the Princesse de Broglie presents yet another scenario. Painted thirty years after the portraits of the Leblancs, its richly embellished frame offers a veritable garden of flowers and is of a type which the artist seems to have particularly liked: floral decoration is also the dominant motif of the original frame on Madame Moitessier in the National Gallery, London. The floral decoration is plaster rather than carved wood, which is also true of the frames on Ingres’s paintings of M. Bertin, Jeanne d’Arc and Madame Moitessier, and many other 19th century frames. Yet, despite the resemblance of the frame on the Princesse de Broglie to others in which Ingres took a personal interest, it is reported to have been made only shortly before being sold to Robert Lehman in 1958 and is thus would seem to be a modern extrapolation of Ingres’s ideas.

The innovation of embellishing a frame with moulded rather than carved decoration has been ascribed to Thomas Jackson and his son George in London, although in fact it is much older [16]. The Jacksons supplied cast ornament to British framemakers – including the framemaker and art dealer, John Smith, who handled Rubens’s Wolf and fox hunt – thus eliminating the labour involved in carving the ornament for a frame. This ready-made ornament is referred to as compo – short for composition [as used in Britain: a mixture of plaster of Paris, rabbitskin glue, resin and linseed oil; French moulded ornament is more simply made of plaster]. The practice enabled and perhaps even encouraged an inventive if sometimes overwhelming richness of motifs which perfectly suited the opulent interiors of the time. The variety of styles, reprising and combining elements of style from Rococo to Empire, and employing floral and other botanical motifs, is readily visible in The Met’s collection.

Gustave Courbet (1819-77), The source of the Loue, 1864, o/c, 99.7 x 142.2 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Théodore Rousseau (1812-67), The forest in winter at sunset, c.1846-67, o/c, 162.6 x 260 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

A few conspicuous examples of French moulded plaster ornament can be found on the frames of Delacroix’s The abduction of Rebecca; Courbet’s The source of the Loue and Portrait of Madame Auguste Cuoq; and Théodore Rousseau’s An early summer morning in the forest of Fontainebleau and The forest in winter at sunset, the latter of which remained with the artist until his death in 1867. It was then acquired by the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922), who became so influential not only as a dealer of pictures – he was a principal source for the Havemeyers, Henry Clay Frick and Albert Barnes, among others, and thus a key figure for The Met, the Frick Collection and the Barnes Foundation – but in providing the frames for them.

Jean-François Millet (1814-75), Haystacks: autumn, c.1874, o/c, 85.1 x 110.2 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Further examples of moulded plaster ornament decorate the Rococo revival frame of Millet’s Haystacks: Autumn, and the Salon frame on his Autumn landscape with a flock of turkeys, with its acanthus and bay leaf mouldings; the latter painting was purchased by Durand-Ruel directly from the artist in 1872.

Eduard Manet (1832-83), Young man in the costume of a majo, 1863, o/c, 188 x 124.8 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Manet’s Young man in the costume of a majo was also purchased from the artist by Durand-Ruel and has a Régence-revival frame with sculptural trellis ornament enriched with florets covering the rails[17].

Leon Bonnat (1833-1922), An Egyptian peasant woman and her child, 1869-70, o/c, 186.7 x 105.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The frame on Bonnat’s Egyptian peasant woman and child is a Second Empire NeoClassical revival frame, the scotia decorated with an enriched ribbon guilloche and the top edge with a garland of bay leaf-&-berry; it is similar in its motifs and style to but much finer than the frame on Rousseau’s Forest in winter.

Renoir (1841-1919), Madame Charpentier & her children, 1878, o/c, 153.7 x 190.2 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The frame of Renoir’s great portrait of Madame Georges Charpentier with her children Georgette-Berthe and Paul-Émile-Charles deserves especial mention for its richly articulated profile and combination of decorative motifs, including acanthus leaves rendered in relief, an ornamental Orientalist frieze, and a stylized leaf-&-dart with a plain sight edge. The Museum acquired the painting directly from the estate of the publisher Georges Charpentier, who had commissioned it from the artist in 1878. It was shown the following year at the Salon, where elaborate, gilded frames such as those surveyed above were de rigueur.

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), Basket of flowers, 1848-49, o/c, 107.3 x 142.2 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Despite the advantages of compo frames, some artists still preferred antique ones where they were available. In 1827, Delacroix wrote,

‘I have finished an ‘animal’ picture for the General and I have found for it a Rococo frame which I’m going to regild and which will be marvellous’ [18].

This is unsurprising in an artist haunted by the achievement of his Old Master heroes – particularly Rubens – and who had as his maternal grandfather Jean-François Oeben, the great 18th century French cabinetmaker. His Basket of flowers – another work which passed through Durand-Ruel’s hands – has a heavily regilded Rococo frame perfectly complementing its NeoRococo composition, which in its open brushwork and swirling composition is reminiscent of the work of Fragonard. Renoir, too, is known to have preferred that his pictures be displayed in antique frames and, like Delacroix, had a particularly soft spot for those which were Rococo in style. Indeed, his son – the filmmaker Jean Renoir – recalled that,

‘When his old friend Durand-Ruel reproved him for having done the portrait of a certain lady for a price that lowered its value, Renoir replied,

‘She promised to put it in a genuine Louis XV frame that I saw at Grosvalet’s’.’

His portraits in The Met are all appropriately in Rococo or Rococo revival frames.

Michele Gordigiani (1835-1909), Portrait of Marianna Panciatichi, marchese Paolucci delle Roncole, 1864, o/c, 64 x 52 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

A fascinating example of the importance Italian frames could assume is Michele Gordigiani’s 1864 portrait of Marianna Panciatichi, for which an incredibly elaborate frame – a fantasy, loosely based on the 17th century grand ducal frames in Palazzo Pitti – was commissioned from a leading Florentine wood carver, Niccola Ricci (fl.1848–1866). Carved and gilded, with silk velvet elements, it overwhelms as well as outclasses the portrait it was meant to embellish.

Framing modernity in 19th century France and beyond

Degas had a very different view of frames from Delacroix and Ingres; one untinged by nostalgia for the elegant artifices of the ancien régime or the conventions governing framing at the Salon. In her Memoirs of a collector, Louisine Havemeyer recounts how, in 1871, when she was just sixteen, Mary Cassat took her to view a pastel by Degas at a colour shop: Rehearsal of the ballet (now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum). It was in a notably simple frame which had been designed by the artist and which Louisine describes as painted a ‘soft dull gray and green’. She recalled that on another occasion – after having again visited the artist in the company of Mary Cassatt – the artist explained to her that,

‘…he wished the frame to harmonize and to support his pictures and not to crush them as an elaborate gold frame would do’.

Ford Madox Brown (1820-93), The convalescent, 1872, pastel/paper, 46.7 x 44.1 cm., 1872, Metropolitan Museum, New York

D.G. Rossetti (1828-82), Ecce Ancilla, 1849-50, o/c, 73 x 41.9 cm., Tate Britain

The design, consisting of a broad, flat frieze bordered by a raised outer edge, was inspired by the innovative frames of Pre-Raphaelite painters like Ford Madox Brown and Dante Gabriele Rossetti [19].

Master of St Ursula Legend (fl. late 15th century), Madonna & Child with St Anne presenting Anna van Nieuwenhove, 1479-82, o/panel, dimensions with engaged frame 59.9 x 45 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

These in turn recall the frames found on some early Netherlandish paintings, such as the Madonna & Child with St Anne by the so-called Master of the St Ursula Legend.

Whistler (1834-1903), Symphony in grey & green: The ocean, 1866, o/c, 80.7 x 101.9 cm., and detail of right-hand side, The Frick Collection

Whistler, who moved from London to Paris in 1859 and had his own strong views about frames, may have been a conduit for the ideas of his British confrères, including those of his mentor, Albert Moore. Pissarro and Monet were in touch with these same British artists during their stay in London during the Franco-Prussian war, and in 1894 Pissarro explicitly described the frames he was having made by the Parisian frame-maker Pierre Cluzel as ‘in the English style’ (‘dans le genre anglais’). Simple rather than complex in profile, without decorative embellishment, and often painted rather than gilded, these architrave frames – as they are called – attracted much comment at the various Impressionist exhibitions, since they marked a rejection of the kind of heavy, historicizing frames with brilliant gilding which were common in the Salon exhibitions.

Degas (1834-1917), The collector of prints, 1866, 53 x 40 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

In his comments on the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition of 1881, the journalist and critic Jules Arsène Arnaud Claretie noted that the frames seemed as revolutionary as the paintings they adorned. Alas, few of Degas’s original frames have come down to us, for as so often in the past, these simple but innovative painted frames were replaced with more conventional ones, either by dealers or collectors. This makes the original frame on Degas’s The collector of prints – in this case gilded rather than painted – all the more notable. The picture was painted in 1866 and predates a drawing Degas made of a profile very like that of the frame. However, the picture remained in his studio and by the time the Havemeyers saw it 25 years later, it was in the frame we see today (the reverse bears the label of Cluzel). They purchased it and had it sent to New York by Durand-Ruel.

Degas (1834-1917), Woman ironing, 1873, o/c, 54.3 x 39.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

A nearly identical frame contains the 1873 pastel A woman ironing. In this case the frame was made not in Paris but in New York, where in 1894 the Havemeyers purchased the pastel at Durand-Ruel’s American gallery.

Degas (1834-1917), Madame Théodore Gobillard, 1869, o/c, 55.2 x 65.1 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The frame on Degas’s Mme Théodore Gobillard, which Mrs. Havemeyer acquired in 1916 through Mary Cassatt, was also made in America. Cassatt, like Degas, experimented with coloured frames and one wonders if perhaps she advised that this one be painted a bronze colour.

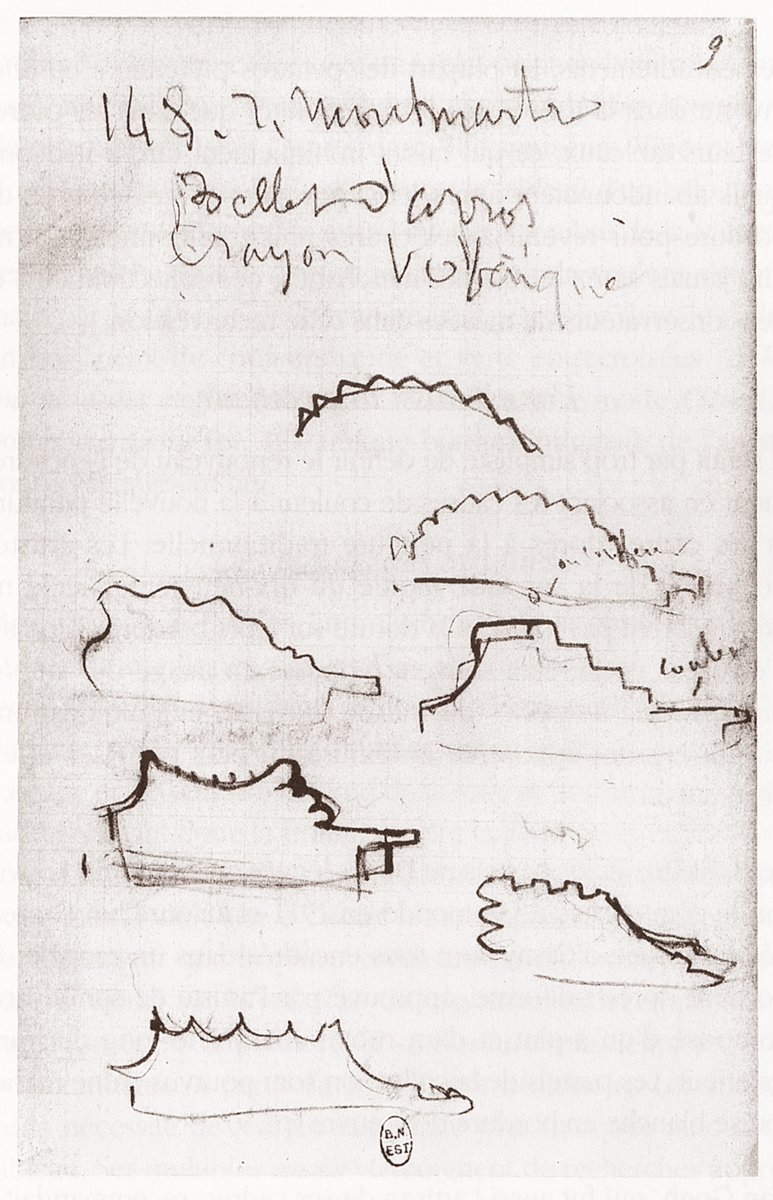

Degas (1834-1917), profiles of frames, Carnet de croquis no 23, Département des Estampes, Bibliothèque nationale, Paris

Degas (1834-1917), Sulking, c.1870, o/c, 32.4 x 46.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Degas made drawings of many different profiles and types of frames. A handsome variant of the architrave frame, employing a ripple pattern reminiscent of 17th century Dutch frames, is on Sulking. According to the dealer Ambroise Vollard,

‘One of his favourite models of frame was Crête de coq – or coxcomb – which had a serrated edge, as the name indicates. Degas also reserved the right to select the colour of his frames, being partial to the bright shades used for painting garden furniture. Whistler called them ‘Degas’ garden frames’.’

Degas (1834-1917), Woman with a towel, 1894 or 1898, pastel/paper, 95.9 x 76.2 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The frame on his 1894-98 pastel Woman with a towel, purchased by the Havemeyers from the artist through Durand-Ruel, is of Degas’s design and is composed of a narrow moulding with layered, irregular projections, made possible by a new technique – pâte coulante – of working with plaster.

Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), Madame Thadée Natanson, 1895, o/cardboard, 62.2 x 74.9 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Pissarro (1830-1903), Two young peasant women, 1891-92, o/c, 89.5 x 116.5 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Yet another frame related to Degas’s designs has a simple curved profile with grooves – a reeded cushion frame – and is commonly gilded, as on Toulouse-Lautrec’s Madame Thadée Natanson and Pisarro’s Two young peasant women. Degas, like Pissarro and others, relied on an established relationship with specific framemakers for realizing and adapting his ideas. In the case of both artists, it was Pierre Cluzel, whose ‘âme généreuse’ Pissarro extolled. In 1888, Toulouse-Lautrec requested Durand-Ruel to send the drawing he had left with the dealer to Cluzel for framing, and the reeded cushion frames on the Toulouse-Lautrec and Pissarro above may have been produced by Cluzel, who died prematurely in 1894. For his part, Ambroise Vollard declared that Père Lézin was the only framemaker whom Degas really trusted (it has been estimated that at the time in Paris there were a hundred and fifty framemakers).

It was through Durand-Ruel that the Havemeyers purchased many of their Impressionist paintings, and it is Durand-Ruel’s ideas about the rôle of frames in marketing the paintings he handled which pervade the Havemeyer collection at The Met. Durand-Ruel realized that these avant-garde paintings would have a greater market potential if their frames related in some way to the fashionable interiors in which they would hang, and he followed this conviction in spite of the objections sometimes raised by the artists. At one point, exasperated, Pissarro wrote to his son,

‘You saw how I fought with him [ie. Paul Durand-Ruel] for white frames, and finally I had to abandon the idea. No! I do not think that Durand can be won over.’

Georges Seurat (1859-91), Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884-86, o/c, 207.5 x 308.1 cm., Art Institute of Chicago

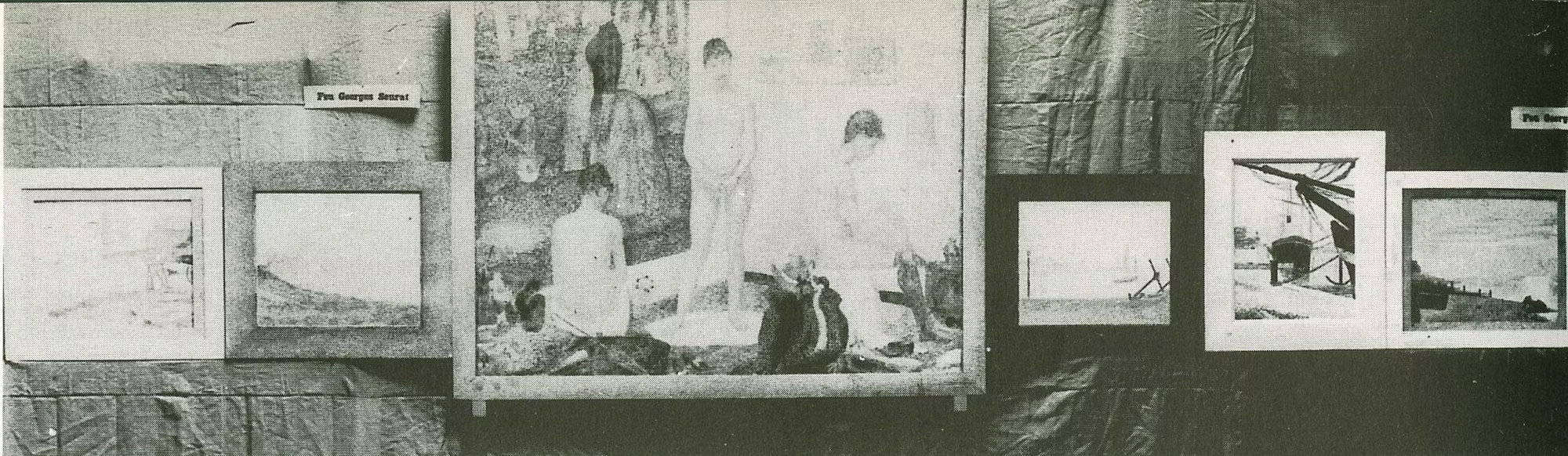

Examples of Seurat’s own frames for his paintings in the exhibition, ‘Neuvième exposition annuelle des XX’, Brussels, 1892; Art Institute of Chicago

The impact of a simple white frame on a large picture is perhaps best appreciated today at the Art Institute of Chicago, where a white frame for Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte has been reconstructed – the original was removed long ago [when Seurat added a painted border to the picture, taking the canvas off its first stretcher to enlarge the pictorial surface. The current frame is based on the evolution of his frame profiles seen, for example, in the photograph above, of his posthumous exhibition in 1892 [20].]

The music room by Tiffany, Havemeyer house, New York

Mrs. Havemeyer may have lamented, in her Memoirs of a collector, the heavy Louis XIV-style interiors fashionable in New York apartments – their own palatial residence on Fifth Avenue and 66th Street had been decorated by Tiffany – but she seems to have seen no unbridgeable contradiction between the way that Degas and Pissarro wished their works to be framed, and the far more conventional frames on so many of the paintings she displayed in the skylit picture galleries constructed around a central staircase.

Manet (1832-83), Boating, 1874, o/c, 97.2 x 130.2 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Manet’s Matador, his Young man in the costume of a majo (illustrated above) and Mademoiselle V. . . in the costume of an Espada, are in fundamentally traditional frames – ready for the Salon, where Manet preferred to exhibit. Manet’s Boating, which the Havemeyers purchased from Durand-Ruel in 1895, and Monet’s La Grenouillère both have antique Régence frames.

Degas (1834-1917), The rehearsal of the ballet onstage, c.1874, o/watercolour/pastel on paper, board & canvas, 54.3 x 73 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

For works by Degas and others, and evidently with Degas’s support, Durand-Ruel adapted a simple type of Louis XVI-style, NeoClassical revival moulding, which originally had been much used in the 18th century for framing drawings. The architrave frame that Degas preferred, the ribbon-&-stave moulding at the top edge and the flat frieze, sometimes with a step, make a nod to modernity, whilst recycling an historical style. This was one of two patterns which became known as ‘Durand-Ruel frames’ and understandably proved very versatile. Examples of the Louis XVI-style can be found on some of Degas’s pastels in The Met, including The rehearsal of the ballet onstage from the Havemeyer collection and The dance class from the Bingham collection. Both had passed through the hands of Durand-Ruel, who clearly knew his collectors.

Impressionist Exhibition at Grafton Art Gallery in 1905, Archives Durand-Ruel, Paris

A photograph of the 1905 Impressionist exhibition he arranged in London shows virtually all the paintings in this type of frame. The use of a common setting suggests an aesthetic shared with collectors of the past, sympathetically unifying as well as giving identity to a collection, whilst intentionally not competing with the painting for attention. In some respects, this spare but elegant frame became to the late 19th and early 20th century what the cassetta had been to the 16th and early 17th century and the Salvator Rosa frame to the 18th century.

Ambroise Vollard, the great promoter of Cézanne and Picasso, took another tack and often favoured antique frames – Italian rather than French, and thus bolder in their geometry and lacking the potential distraction of corner and centre accents. Picasso’s portrait of Gertrude Stein is in a 16th century Italian cassetta, which worked well in the writer’s Paris apartment with its Renaissance furnishings. This type of frame became incredibly popular with collectors and dealers in both Europe and America and remains popular today.

Cézanne (1839-1906), The Gulf of Marseilles seen from L’Estaque, c.1885, o/c, 73 x 100.3 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Cézanne’s The Gulf of Marseilles, a Havemeyer purchase in 1901 from Ambroise Vollard, has a highly architectural Italian frame of the 16th century.

Van Gogh (1853-90), Cypresses, 1889, o/c, 93.4 x 74 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

In the same way, two works by Van Gogh which were acquired by the Museum in 1949 – Sunflowers and Cypresses – have been given antique Italian frames. These are a far cry from the brilliantly coloured, simple mouldings the artist had experimented with (the only surviving example of this sort of frame is on Quinces, lemons, pears and grapes in the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam).

The experiments of Degas, Pissarro and, later, of Van Gogh and Seurat in the use of coloured frames relating to their pictures was unquestionably novel. But it was not the only way of creating harmony between painting and frame. The remarkable Art Nouveau frame on Alphonse Mucha’s Maude Adams as Joan of Arc is of a piece with the style of the picture, and the Grecian-style Ionic frame of Lord Leighton’s Lachrymae, as well as the classical egg-&-dart moulding and ivory ‘predella panel’ of Franz Stuck’s Inferno, were specifically commissioned by each artist.

Frederic Leighton (1830-96), Lacrymae, 1894-95, o/c, 157.5 x 62.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The beautiful curved Ionic capitals on the Lachrymae frame were taken by Leighton from the Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassae, which he knew through an example at the British Museum as well as through the publications and architecture of Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863) [21]. The frame may suggest a doorway out of a temple leading to the place where the painted funeral altar stands, and is thus integral to the subject of the picture. In certain respects, these various approaches mark a return to an older period when frames intimately bound to the work of art were the norm rather than the exception – which will be the subject of the third part of this series.

*******************************************

This is the second of three essays forming a series under the title: ‘Framing the Collection of European Paintings at The Met’. The first provides an introduction and explores the 16th -17thcentury collection, and can be found here. The third will address paintings from 14th -16th century Europe.

A specialist in Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, Keith Christiansen was curator and, from 2009 to 2021, chairman of the Department of European Paintings at The Metropolitan Museum.

*******************************************

Selected reading:

In addition to the many indispensable essays by various authors on The Frame Blog, the following books and essays have been particularly important sources for these three essays. I would especially like to thank Timothy Newbery for sharing his incomparable knowledge of the frames in The Met’s collection.

Reinier Baarsen, ‘Herman Doomer, ebony worker in Amsterdam’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 138, no 1124, 1996, pp. 739-49

Isabelle Cahn, ‘Degas’s frames’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 131, no 1033, 1989, pp. 289-93

Fédéric Destremau, ‘Pierre Cluzel (1850-1894), encadreur de Redon, Pissarro, Dégas, Lautrec, Anquetin, Gauguin’, Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art français, 1995, pp. 239-47

Elizabeth Easton & Jared Bark, ‘Pictures properly framed: Degas and innovation in Impressionist frames’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 150, no 1266, 2008, pp. 603-11

Helen Gramotnev, ‘Degas’s frames for dancers and bathers’, The Frame Blog

Peter Mallo, ‘Artists’ frames in pâte coulante: history, design, and method’, Metropolitan Museum Journal, 56, 2021, pp. 160-73

Claude Mignot, ‘Le cabinet de Jean-Baptiste de Bretagne: un ‘curieux’ parisien oublié (1650)’, Archives de l’art français, n.s. 27, 1984, pp. 71-87

Paul Mitchell & Lynn Roberts, A history of European picture frames, London, Paul Mitchell in association with Merrell Holberton, 1996

Timothy J. Newbery, George Bisacca, Laurence B. Kanter, Italian Renaissance frames, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990

Timothy Newbery, Frames, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in association with Princeton University Press, 2007

Nicholas Penny, ‘Reynolds and picture frames’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 128, no 1004, November 1986, pp. 810-25

Nicholas Penny, ‘Notes on frames in the exhibition, Portraits by Ingres’, exhibition review, February 1999, accessible on the National Portrait Gallery website

Nicholas Penny & Karen Serres, ‘Duveen and the decorators’, The Burlington Magazine, 149, 2007, pp. 400–06.

Nicholas Penny & Karen Serres, ‘Duveen’s French frames for British pictures’, The Burlington Magazine, 151, 2009), pp.388–94

Gemma Plumpton, ‘Framing the Renaissance’, on the Harewood House website

Bruno Pons, ‘Les cadres francais du XVIII siècle et leurs ornaments’, Revue de l’Art, no 76, 1987, pp. 41-50, translated as ‘18th century French frames and their ornamentation’ on The Frame Blog

Karen Serres, ‘Duveen’s Italian framemaker, Ferruccio Vannoni’, The Burlington Magazine, 159, May 2017, pp. 366–74; and ‘19th & 20th century Italian framemakers: articles in The Burlington Magazine’ on The Frame Blog; further information on Duveen’s reframing can be found in the Duveen Files, available through the Getty website

Antoine Schnapper, ‘Bordures, toiles et couleurs: une révolution dans le marché de la peinture vers 1675’, Bulletin de la Societé de l’histoire de l’art français, 2000 & 2001, pp.85-104

Pieter J.J. van Thiel & C. J. de Bruyn Kops, Framing in the Golden Age: picture and frame in 17th century Holland, translated by Andrew McCormick, Rijksmuseum, 1995

The entry on John Smith on the National Portrait Gallery website

*******************************************

[1] The other three Longhis in the same frame are The letter, The visit, and The meeting

[2] A female allegorical figure (1984.49) and A female allegorical figure (1997.117.8)

[3] See Jacob Simon, ‘Thomas Gainsborough and picture framing’ for details of when the artist used ‘Maratta’ frames

[4] For Romney’s frames, see Jacob Simon, ‘A note on George Romney and picture framing’

[5] Oeben’s mechanical table created for Madame de Pompadour is now in the collection of the Museum

[6] From Bruno Pons, ‘18th century French frames and their ornamentation’, translated from ‘ Les cadres francais du XVIII siècle et leurs ornaments’ in Revue de l’Art in 1987 (no 76, pp. 41-50)

[7] See Paul Mitchell, ‘A signed frame by Jean Chérin’

[8] See ‘Jacques-Louis David’s frames: revolution, Empire and beyond’. For Buteux’s frames for the state portraits of Louis XVI, see Sarah Medlam, ‘Callet’s Portrait of Louis XVI: A picture frame as diplomatic tool’, Furniture History Society Journal, vol. XLIII, 2007, pp.143-54

[9] Sarah Medlam, ibid., p. 148-50

[10] See the online catalogue entry, under ‘Frame’

[11] ‘Jacques-Louis David’s frames’, ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] See ‘What artists, critics & collectors say about frames: Part 3’

[14] See also Louise Delbarre, ‘The exhibition Regards sur les Cadres, and the frame collection of the Louvre’ (June-November 2018)

[15] See ‘How Pre-Raphaelite frames influenced Degas and the Impressionists’

[16] See, for example, ‘National Gallery, London: a Venetian pastiglia frame’

[17] The painting passed through Durand-Ruel’s hands in 1872-77 and 1898-99; this frame was probably applied before it was sold to the Havemeyers of New York in 1899, possibly using the same carvers and gilders who supplied the Duveen brothers. By the 1920s Duveen was using a frame supplier named ‘Joubert’ (see Karen Serres & Nick Penny, ‘Duveen’s French frames for British pictures’, Burlington Magazine, June 2009, vol.151), probably Félix Joubert la Tourelle (1872-53) of the King’s Road, London , although he may have been fractionally too young to have framed the Manet Young man… In 1945 Duveen was using ‘Bourdier’, probably the E. Bourdier of 67 boulevard de Courcelles, Paris; but whether this Bourdier was operating in the late 19th century is open to question, as he seems to have escaped research of any kind:

Other framemakers used by Duveen include ‘Boullanger’, who also worked for the Louvre (Serres & Penny, ibid.) and Cadres Lebrun, founded in 1847 and still owned by the same family. Durand-Ruel might have used any of these to reframe the Manet, since their expertise is evident in the frames commissioned by Duveen

[18] Delacroix, Eugene Delacroix: Selected letters 1813-63, transl. Jean Stewart, 1971. See ‘What artists, critics & collectors say about frames: Part 3’ for the probably painting, and a montage of it in a randomly-chosen Rococo frame

[19] See ‘How Pre-Raphaelite frames influenced Degas and the Impressionists’

[20] Charles Stuckey describes the series of frames made for La Grande Jatte in ‘True colors: Seurat and La Grande Jatte’, Art in America, 1 November 2004